The Know How: The Case of the Curious Overlander

Also: Cold hard facts on freezing, the juice on staying juiced.

Image Caption: Illustration Courtesy of Todd Detwiler

Q: I keep hearing about overlanding. I’m interested to try, but I don’t know if I’m ready to invest in a vehicle. What’s a good first move?

A: I built my first “overland” vehicle at age 20, before anybody called it overlanding. Back then, in the 1960s, it was just plain old camping. I bought a used four-wheel-drive Suburban on the cheap and installed a fold-down bunk that doubled as a sofa, a fold-down table, and window screens with room-darkening curtains. A Coleman stove, a portable picnic table, water containers, and a tarp that tied to the roof rack as an awning: my rig was complete. It took me all over the country.

People still take this same DIY approach, along with more elaborate conversions on Sprinter and Transit vans and the like. If you have a limited budget but an appetite to experiment, this path is still very much available—as are used, low-cost Suburbans and other four-wheel-drive vehicles that allow you to get into more remote areas and public lands that have become synonymous with overlanding.

Research, too, can open this world for you. Overlanding vehicles run the gamut from motorcycles to vans and pickups to huge, heavy trucks that cost six or seven figures. The Overland Expo events around the country showcase vehicles and the many accessories available. You could rent a vehicle to try it out. Overland Journal and other magazines (including this one) help define the practice of heading out into the deep country in a vehicle made for the task.

Illustration Courtesy of Todd Detwiler

Q: I’m taking my Class C motorhome to a weeklong pond-hockey tourney in New Brunswick, Canada, in February. I’ve never parked it in an icebox before. What do I need to know?

A: Depends. Will you be at a campground with electricity, at least, or simply be parked in a field? First, find out whether your RV is a true four-season rig, which means (among other things) it has insulated—and possibly heated—holding tanks. If you have electrically heated tanks and can plug them in, you’re in luck. If you have them without electric hookups, you’ll need to run your generator much of the time when it’s below freezing to keep the tanks warm.

If you have insulated tanks that get their only heat from the coach interior, you’ll have to run the furnace a lot. This uses up propane fast—and the furnace fan motor runs the battery down in a few hours. So you’ll have to keep an eye on propane and fuel supplies unless you have electricity to plug into and can run an electric heater.

If you have a water hookup, fill your freshwater tank (if the tanks are protected from freezing) and then disconnect the hose (it will freeze). Use your onboard water pump. The water heater won’t freeze if it is full and lit. If your tanks are not protected, you may have to rely on water jugs stored inside the coach for cooking, washing, and flushing. If you have bathroom facilities nearby, use them. If not, you may need to pour some RV antifreeze into the drains and toilet to prevent tank freezing.

Suffice to say; there’s a lot to winter camping. It’s best to read up on it.

Illustration Courtesy of Todd Detwiler

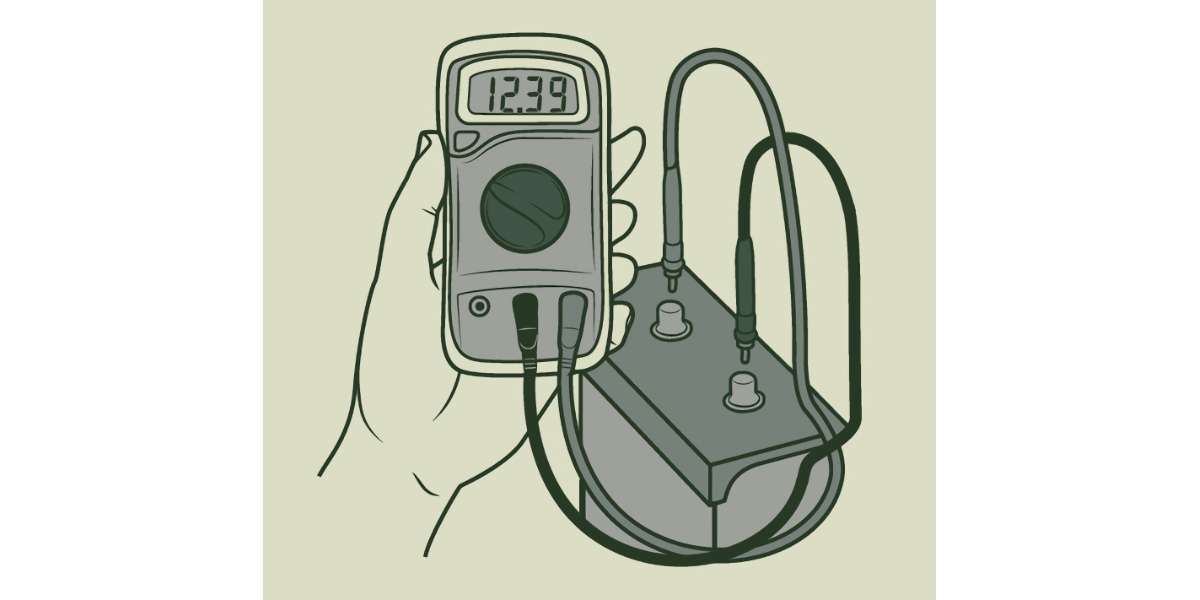

Q: What are some tips for maintaining RV battery life

A: The most important action you can take is to avoid deep discharges. A conventional lead-acid battery’s life gets a lot shorter if its charge level is left at 50 percent or less.

Pay attention to the battery charge-level monitor—or add one if you don’t have one. Learn how to interpret it. If your 12-volt battery is fully charged, the monitor will read 12.6. At 75 percent, it reads 12.4. If you’re seeing 12.2 or less, that puts your battery in the danger zone. Many RV campgrounds have 120-volt AC power, and plugging into that source should maintain your charge via the onboard power converter.

Make sure the battery terminals are kept clean and tight. Also, check the battery electrolyte level every few months if the batteries have removable caps. Add distilled water only up to the internal level indicator—don’t overfill. AGM (absorbent glass mat) and lithium batteries don’t require this.

Lithium batteries can be discharged more deeply without damage, but require a special charger to safely recharge them. When camping without hookups—a.k.a. dry camping—solar panels are popular, but they require a solar-charging control unit.

Portable generators are the other popular way to recharge batteries when dry camping. They can also power devices that consume a lot of current, such as air conditioners and microwaves. Just be considerate of neighbors, campground rules, and quiet hours. If you find that you are running out of power when dry camping, consider adding one or more batteries. Try to match the brand and type of batteries so they work together properly.

Ask Us Anything

Questions about your road-trip ride? Write us at [email protected]. Visit rv.com for more on RV gear and maintenance.

This article originally appeared in Wildsam magazine. For more Wildsam content, sign up for our newsletter.