Know-How: Getting Dinghy With It

A guide to dinghy towing: How to get started, how to stop (literally), and more.

Image Caption: Illustration by Todd Detwiler

Ship Ahoy: The Dinghy Defined

Travel down the American road lately, and it seems that just about every RV on the move is towing another vehicle. This tactic opens up new possibilities on many kinds of journeys: the convenience of a smaller ride to navigate city streets, something beefier than your rig for rugged overland adventures!

The key word here is dinghy. Any vehicle you tow behind a recreational vehicle can be called a dinghy, nomenclature borrowed from the nautical world. (In some circles, you’ll see “toad” instead. … You get it, right?) The first thing to figure out is what you want to tow, then whether your proposed dinghy vehicle can be flat-towed (i.e., with all its wheels touching pavement—we’ll get into other towing methods in a sec). Some manufacturers test and approve certain vehicles and option packages as flat-towable if directions are followed. Check the owner’s manual—before you buy, ideally. Small differences in option packages may determine whether a vehicle is towable— and sometimes vehicles aren’t advertised as dinghy-friendly, but their manuals reveal that they are.

Some rules of thumb: In general, full-time four-wheel-drive or all-wheel-drive vehicles are not flat-towable. Neither are most electric vehicles or real-wheel drives. Fortunately, there are quite a few models approved for towing, including some front-wheel drives with manual gearboxes, some front-wheel drives with automatic transmissions, and many four-wheel drives that have transfer cases, which can be shifted into neutral for towing.

An important note: If you try to tow a vehicle that’s not designed for it—or if you don’t take all the proper steps—you can damage your would-be dinghy in expensive ways that your warranty won’t cover. So make sure you ask all the questions and read up!

Photo Credit: Curt

Carry That Weight

As you might expect, weight is a key factor in dinghy towing. With the exception of some large diesel pushers and a few other heavy-duty models, many motorhomes have a fairly limited towing capacity: around 5,000 pounds. Motorhome manufacturers often publish tow ratings in their specs.

Another way to determine a tow rating is to subtract the actual fully loaded weight of the motorhome—including passengers, cargo, full fuel, and liquids—from the gross combination weight rating (GCWR). This gives you the towing capacity. For example, if the GCWR is 30,000 pounds, and the actual loaded weight is 25,000 pounds: Voilà, you have 5,000 pounds available for towing.

Photo Credit: Hopkins Towing

The ABCs on ABS

Towing a vehicle that weighs thousands of pounds (or kilograms, if you’re north of the border) without brakes could make it much harder to stop, causing the motorhome to skid and perhaps jackknife and/or possibly overheat the brakes, which could lead to complete brake failure.

Not good! So auxiliary dinghy braking systems are required by law in most states and provinces. These address a couple of knotty technical problems. First, when you’re towing a vehicle, obviously, its engine is off. That means its brakes aren’t powered. So auxiliary braking systems are designed to exert a lot of pressure on the dinghy’s brake pedal when it’s time to stop. The second trick is getting the force to sync with the motorhome’s own brake. Ideally, the dinghy brakes the same amount as the motorhome in all conditions.

Over the years, various manufacturers have developed designs to meet these challenges. Many use inertia accelerometers to determine the rate of motorhome braking, which signals the ABS to match that rate. These typically use an electrical servo motor to apply the brakes and draw a fair amount of current from the battery. Depending on the type of ABS you choose, you may need a special charging line from the motorhome’s alternator to keep the dinghy vehicle’s battery from running down.

Dinghy Braking Systems of Note:

- Demco Stay-in-Play: Syncs the dinghy brakes by monitoring the mothership’s brake lights. $1,175

- Demco Air Force One: As the name suggests, for air brakes. Monitors a brake-system pilot signal. $1,329

- Roadmaster 8700 Invisibrake: Promises a “set it and forget it” experience, working via existing wiring between towing vehicle and dinghy. $1,175

- Roadmaster 9160 Brakemaster: Controlled by brake-line pressure. $1,075

- Blue Ox BRK2019 Patriot 3: Operates via wireless remote control. Works with hybrids. $2,017

- Hopkins Towing Solutions Brake Buddy Classic 3: Selling points include ease of install, system that prevents tire flat-spotting. $1,149

- NSA ReadyBrake: A mechanical pressure brake that mounts to the trailer hitch. Simplicity is the attraction. $830

- RVibrake 3 Portable Flat Towing Braking System: The high-tech end of the spectrum, with a touchscreen control tablet, wireless inertial activation, and an audio setup assistant. $1,595

Photo Credit: Getty

Deep Dive: Towing Methods

Get to know the three popular ways to tow a dinghy vehicle behind a motorhome: with a trailer, with a tow dolly, or flat-towing with four wheels on pavement. Each, not surprisingly, comes with pros and cons.

Trailers

A trailer allows you to tow any vehicle completely up off the road, so there’s no wear and tear on the dinghy. Any type of drivetrain can be accommodated, and if you use an enclosed trailer, you can protect the dinghy from the elements, vandals, rock chips, etc.

So why do anything else? Well, trailers are costly, heavy, and may reduce the weight you can tow. Many motorhomes also have limited tongue weight capacity, often around 500 pounds. Loaded hitch weight should be 10 to 12 percent of the total loaded trailer weight. You can get aluminum trailers, which are lighter, but they’re even pricier; a nice trailer will add thousands to your towing costs. And some campgrounds may have limitations on vehicles per space: park the trailer and unload the dinghy, and that makes three vehicles by Mister Ranger’s count.

Dollies

Tow dollies are basically two-wheel trailers that allow you to tow a vehicle with the front wheels off the road. Dollies allow front-wheel-drive vehicles that aren’t approved by their manufacturer for flat-towing to become dinghies. Trailers and dollies have brakes and lights, saving you from having to add them to your dinghy vehicle. Dollies don’t take up much space at a campground, and they’re generally lighter and less expensive than trailers.

Flat-Towing

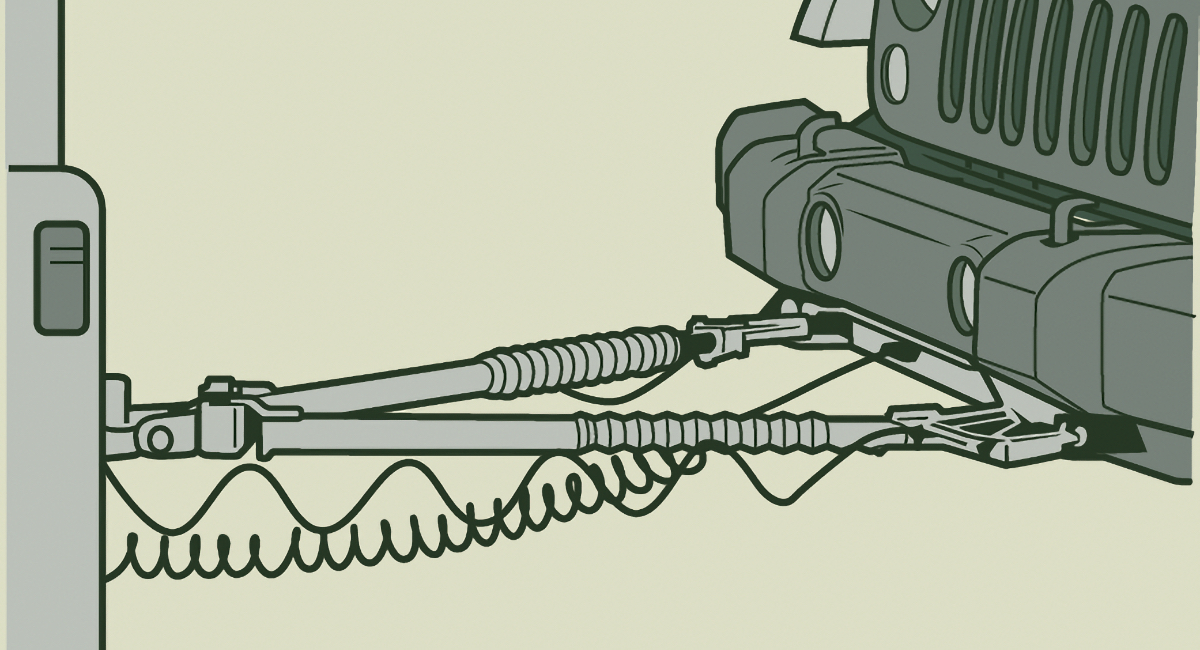

In order to safely and legally flat-tow, you need, at minimum: a tow bar, safety cables or chains, a baseplate, an auxiliary dinghy braking system, a breakaway switch (connected to the ABS), and rear lighting (including tail and brake lights, turn signals, license-plate light and side markers). It’s a lot, and worthy extras include some sort of rock-and-gravel guard to protect the dingy’s paint and windscreen. Many vehicle manufacturers also require certain fuses be removed during towing—there are aftermarket kits to simplify this.

Illustration by Todd Detwiler

Wiring: Will DIY Turn Out A-OK?

Prepping a dinghy vehicle typically requires several electrical tasks. These can include running a cable with a plug that connects to the motorhome, hooking up lights, installing a breakaway switch, providing power to the auxiliary braking system, and, in some cases, wiring a switch so you don’t have to do contortions to reach the fuse panel to remove fuses. Diodes (which are basically electrical check valves) are often installed to feed power from the motorhome lights to the existing rear lights, preventing back-feed problems that can cause trouble in the electrical system.

Doing these jobs yourself can save hundreds of dollars. And each task, taken separately, probably isn’t too daunting if you’ve ever done some wiring around your RV, car, or home. By doing each step separately in a logical sequence, most DIYers should be fine. It’s a lot, though, if you’re not too electrical-savvy. In that case, go to the pros.

Photo Credit: Getty

Voices From the Road

Among Friends

“Before we bought our 2007 Keystone Montana, I was on the Montana Owners Club online forum every day, every time I got a break at work. All these years later, I’m still on there about twice a week. Just about every topic you can imagine gets covered: How to buy, how not to buy, where to go, where not to go, how to prevent and solve any problem you can think of. If you go on there with a specific issue, you’ll have a half-dozen responses in 24 hours. You’ll see a moderator say, ‘Oh yeah, that year’s model used this kind of converter. … It’s amazing.” —John Johnson, San Antonio, TX

Pressure Drop

When Steve Lente of Colorado Springs bought the 17-foot travel trailer he’d dubbed “Lorelei,” he did the prudent thing by installing an aftermarket tire-pressure monitoring system. (RVs have some distinctive tire issues—and sensors onboard a towing vehicle offer no insight on the RV behind it.) It came in more than handy one day on I-10 in Houston. “I don’t know if you’ve been through Houston,” he says, “but I-10 has been under construction for 50 years.”

In the middle of a tangle of traffic and roadside barriers, his TireMinder system indicated an alarmingly steady pressure drop. “We were watching the numbers go down and down. My wife was doing the driving; I was doing the math.” Fortunately, thanks to this real-time data, they made it to an off-ramp in time to seek a fix before a blowout.

Bleach Prospects

Q: We’re first-time RV owners about to go on our first extended RV trip. What should we do to make sure our freshwater tank is clean? —Sallie Cintron, Torrance, CA

A: Fill the freshwater tank roughly halfway with clean water and add a cup of bleach or specialty RV tank-cleaning fluids. Then, take your rig for a short drive to get the water sloshing around inside. Park it and let it sit for a few hours. Finally, drain the tank and refill it with fresh water. Repeat the process every six months or so.

Got a question about your road trip ride? Write us at [email protected].

This article originally appeared in Wildsam magazine. For more Wildsam content, sign up for our newsletter.