School kids here have it easy when researching the history of their hometown. It’s found all in one place – the Museum of the Yellowstone in West Yellowstone, Montana. The building was originally the end-of-line depot of the Oregon Short Line Railroad. Next to it is the Union Pacific Dining Lodge, a massive edifice of log and stone, with a fireplace big enough for me to walk around in. Opened for business in 1909, it was in these two-story structures where it all began for this town. And they are what make this place unique.

West Yellowstone did not just drift into Montana like a spoor, as the wild wind of the frontier blew west. It was never a rogue tent city like those that sprouted around gold mines and railroad spurs. It is a town that is now what it has always been.

Situated on the west edge of Yellowstone National Park, it became the chic point of entry for the “jet set” of the early 1900s. It was a time when train travel was elegant, and it was the only way to journey to Yellowstone, the first national park in the country – and in the world, for that matter.

“They would arrive at 7 in the morning on the Yellowstone Special in 40 state-of-art Pullman cars,” Paul Shea told me. He is the curator at the museum. “While porters unloaded their luggage, visitors would gather for breakfast in the great dining hall, all stylishly dressed for a day of touring the park, where they would spend three nights. Some even brought their maids and servants with them. The hotels in the park were magnificent – and even more so today, as they have retained the grandeur of that era. In the early days, they toured by stagecoach, later in open touring cars. Their visits ended here with lavish dinners in the dining lodge.”

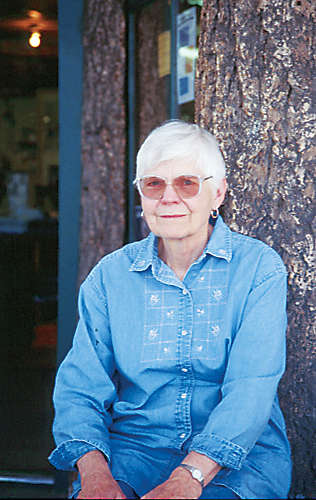

Kay Eagle was a waitress there. “I came from Nebraska, my first year in college – 1947. It was a summer job that was much sought after. You had to know somebody to get it. We came on the train. They gave us room and board. I used to make $20 or $30 a day in tips serving breakfast and dinner. Oh, they were done beautifully – linen tablecloths, wine in glass decanters. We had to wear white, pin-on collars … can you imagine?”

I met Kay in the Eagle Store – a retail institution in town that is now run by third-generation Eagles. They sell western boots, hats, all that sort of thing. We had ice tea together at the Eagles’ soda fountain that dates back to 1914.

After the war, she said, things got more casual in the dining lodge. Its theme went Western in the 1950s. “They switched to red-checked tablecloths and dispensed with our white collars. I was sure happy to see those go. We were serving everybody then, not just train passengers.” Middle America was now on the road and West Yellowstone was adjusting to this new onslaught of tourists.

The Yellowstone Special operated every summer until 1960. Rail service was abandoned here in 1970. Long before that, however, Kay had married one the Eagle boys, given up Nebraska, and was raising a family here.

This area was all national forest then. In 1920, President Woodrow Wilson signed a proclamation removing the town from the Madison National Forest and creating the 49 square blocks that are West Yellowstone. A thousand people live here, providing for the million-plus tourists who pass through every year. Its location defines it. And that’s not likely to change.

Welcome to America’s Outback.

Bill’s e-mail address: [email protected]