I fell in love with the Old West when I was 11 and have never gotten over it. While other girls in my grade-school class were absorbed in romance novels, I was reading Laura Ingalls Wilder and Zane Grey — and it seemed such a shame I’d been born too late to travel west in a covered wagon.

Since we began RVing 20 years ago, my husband, Guy, and I have followed many of the old trails — it’s become quite a passion for both of us. But I had never thought of it as something genetic until we discovered that my great-great-great grandfather Washington Peck had taken his family along the Mormon Trail to the Great Salt Lake en route to the California gold fields.

He had kept a journal of the 1850 trip — a relative gave us a copy several years ago — and we recently followed the route from Council Bluffs, Iowa, to Salt Lake City, Utah, as closely as possible on today’s roads.

The Pecks started from Windsor, Canada, crossing to Detroit, Michigan, where he wrote “We bid farewell to Her Majesty’s Dominions and took up our abode under the Pinions of the Great American Eagle.” Weeks later they reached western Iowa and “stopped at Kanesville … the town at the Bluffs. It is called Council Bluffs for 50 miles. Nearly all the inhabitants… are Mormon.”

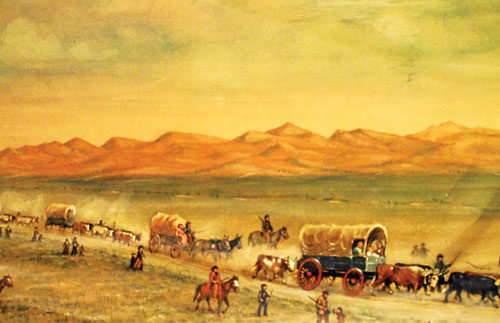

According to the National Park Service, the Mormon Pioneer National Historic Trail begins at Nauvoo, Illinois. Peck wrote that after the Mormons were “dispersed at Nawveaux” in 1846, many of them “squatted at Kanesville (Council Bluffs) till they could acquire the means to go on to the Mormon settlement (Salt Lake City).” That year they embarked on the best-organized mass migration in American history, and over the next 43 years more than 100,000 Mormons journeyed west into what, at the time, was “a land no one else wanted.”

They had been “dispersed” on other occasions: from New York, where Joseph Smith had founded the religion, The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-Day Saints (LDS), in 1830; from Ohio, Missouri, then Illinois. Many were later allowed to return to northwest Missouri after agreeing to abandon “plural marriage,” and today there are numerous LDS historic sites in the area.

We began at Winter Quarters (today’s Florence, Nebraska), where 5,000 Mormons had spent the winter of 1846-47 preparing for the move, the longest leg of their journey at more than 1,000 miles.

Before leaving Council Bluffs today we suggest visiting some of the attractions of this town rich in history of the trails that converged (but did not begin) here: Lewis and Clark, Oregon, Mormon Pioneer and California. The Western Historic Trails Center includes exhibits and information on all of the historic trails that pass through the area. (For more information visit www.councilbluffsiowa.com.)

Mormon Bridge (Interstate 680) crosses into Omaha, Nebraska, where the 15,000-square foot Mormon Trail Visitor Center Historic Winter Quarters is located. Exhibits include films, a log cabin, a replica of the 1841 white-limestone temple in Nauvoo and artifacts such as an ingenious early odometer that accurately measured miles. This was of particular interest to us as Washington Peck had observed one in use on a covered wagon.

Arriving in Nebraska, Peck wrote, “Crossed the turbid waters of the Missouri … stopped and looked back to take a last farewell of civilization, and all the trace that we could discover of it, with all the advantages that cluster around it, was a distant view of an insignificant log hut. Civilization has been fading away for 300 miles…”

Subtly, the West begins here — in the immense sky, land stretched flat to thick groves of trees to the south, wide fields of rough grass. The route passes Elkhart River Crossing (now a recreation area); Fremont State Recreation Area; and the site of a once-famous “Lone Tree.” Peck mentions the tree, a “giant solitary cottonwood, visible for 20 miles.” By 1863 the tree was dead, but it lent its name to a stage station and town later renamed Central City.

For some 500 miles across Nebraska, the Mormon Trail paralleled the Platte River, a lifeline for emigrants such as the Pecks, who “chose the north shore to shun contact with sickly travelers on the south side.” There was less wagon traffic on the north side since the Oregon and California trails ran on the south, and Brigham Young wanted to avoid unnecessary clashes with Mormons coming out of Missouri.

Today’s route runs past Kearney; Lexington, where Dawson County Historical Museum is worth a stop; and Confluence Point, where the North Platte and South Platte rivers join to meander on east. The land seems much as it must have 160 years ago: dried out and empty, rumpled into distant low hills; a lonely, lovely place.

At Sutherland we drove north on Pioneer Trace several miles to the Mormon Monument. A sign explains that Brigham Young and Heber Kimball had scouted the valley seeking a route through “these hills.” Braided ruts still mark the passage of hundreds of wagons descending to the river valley. Now the soil is sun-baked dry, bleached to a pale dim color. Ragged arroyos trench the ground and hills craggy with rocky outcrops hint at grander formations ahead.

We suggest visiting Lake McConaughy, a state recreation area, before proceeding west toward 400-foot high Courthouse Rock and its neighbor Jail Rock, which Peck called “natural curiosities.” A few miles farther is 470-foot high Chimney Rock, a solitary spire and important landmark to early travelers. Today it’s a National Historic Site, administered by the Nebraska State Historical Society, with a fine visitor center. Another geological wonder, Scotts Bluff National Monument, is ahead.

The route crosses into Wyoming, and continues to Fort Laramie National Historic Site. The fort, originally called Fort John, began as a small adobe trading post established in 1841. It was sold to the U.S. government eight years later to become a military fort with up to 600 soldiers. Today many of the original 60 buildings have been restored and are open for tours. There’s also an excellent visitor center/bookstore.

In his July 4, 1850 journal entry, Peck noted their arrival at the fort, “522 miles from the Missouri.” New barracks are being built, he wrote, and “mechanicks [sic] are being paid $60 to $70 per month for the work.”

The fort was sold in 1890, though the store — which has been restored and is stocked with merchandise as it would have been in 1860 — stayed open another 34 years. Now run by the National Park Service, the

site opened to the public in 1938.

Continue west to Register Cliff State Historic Site near Guernsey. Emigrants often carved their names into the soft stone-face: “S.H. Patrick June 6, 1850,” “J.S. Bond 1853,” “R. Nesrit August 2, 1855,” among many others.

Driving west, a long smoke-blue serration seems to pop from the far horizon — the Rocky Mountains. Continue to Casper, Wyoming, where the 25,000-square foot National Historic Trails Interpretive Center is located, one of the finest museums anywhere. There’s an 18-minute video shown on five screens; also life-size dioramas of Native Americans (here at least 9,600 years ago), fur trappers, emigrants, Pony Express riders, and others; a simulated, almost-too-real “river crossing” in a wagon bed; and a replica of the Mormon Ferry river crossing, the first commercial ferry on the Platte, established in 1847. Over the next five years it carried up to 73 wagons a day.

An exhibit points out that most of the 70,000 Mormons walked the 1,031 miles from Winter Quarters to the Great Salt Lake Valley pulling handcarts. A handcart replica includes a treadmill and gauge, so visitors can try pulling the heavy thing to see if they’re slogging along “too slow, a good pace, or too fast.” (I managed the “good pace,” but can’t imagine towing the cart the 371,160 wheel-revolutions it took to make the trip.)

Continue west — through a surreal landscape where pale-blue mountains emerge in far-horizon haze, then seem to float away like mirages — to Independence Rock, named by fur trappers who arrived here in the Sweetwater River Valley on July 4, 1830. Eleven years later Jesuit missionary Pierre DeSmet called the massive granite dome the “great record of the desert.” Some attribute the name of the rock to the fact that emigrant wagon parties attempted to reach the rock by July 4 in order to reach their destinations by the first mountain snowfalls.

Ahead is Devil’s Gate, a towering cleft in the rocks, and Martin’s Cove, where Mormon Handcart Historic Site and Visitor Center is located today. It tells the story of the Martin Handcart Company, a group of about 600 emigrants mostly from England, who had left Florence, Nebraska, late in August 1856. Six weeks later in Wyoming, to lighten their heavy carts, they abandoned clothing and other items — an ill-fated decision, as a fierce winter storm was soon upon them.

Martin’s Cove was among the sites where they took temporary shelter. Eventually, rescue parties from Salt Lake City reached the group — but by the time their journey was over, 150 had died. The center offers handcart treks.

The route continues west to South Pass — pioneers called it the “Cumberland Gap of the West” — which crosses the Continental Divide, elevation 7,550 feet, on a “gentle grade.” Peck wrote: “We crossed the backbone of North America, and if our guidebook had not particularly noted the place we should have passed it without knowing it.”

At Farson near Little Sandy Creek, interpretive exhibits claim that in June 1847 Brigham Young and other Mormon pioneers met with mountain-man Jim Bridger “to discuss the possibility of establishing and sustaining a large population in the Valley of the Great Salt Lake.” Bridger supposedly tried to discourage the venture, offering “$1,000 for the first bushel of corn grown there.”

Just east of Rock Springs the trail joins I-80 and continues to Fort Bridger State Historic Site. Established in 1843, it was originally a “trader’s fort,” Peck wrote, “composed of four log houses and a small enclosure for horses.” The U.S. military took it over in 1858, eventually abandoning it in 1890.

Continue into Utah, where the road, which seems to descend forever, is bordered by massive red-rock bluffs pocked with crevices and caves, bulging with ledges and lobes. An excellent state welcome center in 16-mile-gorge Echo Canyon offers tons of literature about the emigrant route and Utah in general. Points of historical interest along the trail here are numerous: Bear River Crossing, Emigrant Springs, Hogsback Summit and Weber River Crossing.

Ahead (but not on I-80) are Big Mountain Pass and Little Mountain Summit, where hikers today can follow the old trail for several miles and imagine the difficulties of 19th-century travel. Peck calls the route, which continues down Emigration Canyon into Salt Lake Valley “muddy, rocky, stumpy, crooked and sideling.”

Today’s travelers don’t have to deal with the “forests of small timber, and bad mud-holes at creek crossings” that Peck describes, or have to lower their vehicles down near-vertical hillsides with ropes, but even now the road to “Trail’s End” — Salt Lake City — is tortuous and steep.

Peck wrote, “We obtained a view of the southern part of that valley in which the anchor of the Mormon hope is cast for this world. Whither it is sure and steadfast, time alone will tell.”

Salt Lake City’s many sites include: 10-acre Historic Temple Square, Salt Lake Temple and Salt Lake Tabernacle; nearby Museum of Church History and Art; Family History Library; and Brigham Young Monument among others.

But the best place to end the trip is at This is The Place Heritage Park, a 425-acre living history museum on the site where Brigham Young is said to have decided the location of the new town (the “City of the Great Salt Lake,” Peck wrote). A 60-foot monument dedicated on July 1947 commemorates the 100th anniversary of the Mormons’ arrival.

Dozens of donated historic buildings, including Young’s elegant “farmhouse,” have been brought here to recreate a typical mid-19th-century Mormon community. Visitors take self-guided tours and trams are available.

The Peck group stayed in the “City of Latter-Day Saints” for two months, helping with the fall harvest before continuing west, with Peck by then captain of the “29 wagons, 2 carts, 92 men, 9 women and 28 children.” He had noted that “Mormon emigration will be heavy, but with prudence, provisions will be sufficient for the wants of the people.”

The next 160 years would show that the “Mormon hope” he wrote of was indeed “sure and steadfast.”

For information about the Mormon Trail visit:

www.visitnebraska.gov

www.wyomingtourism.org

www.utah.travel

www.blm.gov