Across the Cowboy State, the promise of riches drew pioneering miners to seek their fortunes in precious metals. The once-bustling mining settlements now preserve a vibrant chapter of frontier history. Step back in time as we take you to some of Wyoming’s best-kept ghost towns

The Cowboy State offers many opportunities for summer travelers. There’s world-class fishing in its lakes and rivers, hiking and rodeos, mountain and ranch vistas, wildlife viewing, rafting, hot springs, seasonal festivals, Yellowstone National Park — and 70 ghost towns. At one extreme, many of these historic sites are little more than decaying logs, a few crumbling foundations and perhaps an old well gone dry. At the other extreme, they are fully curated campuses restored to their original livable state.

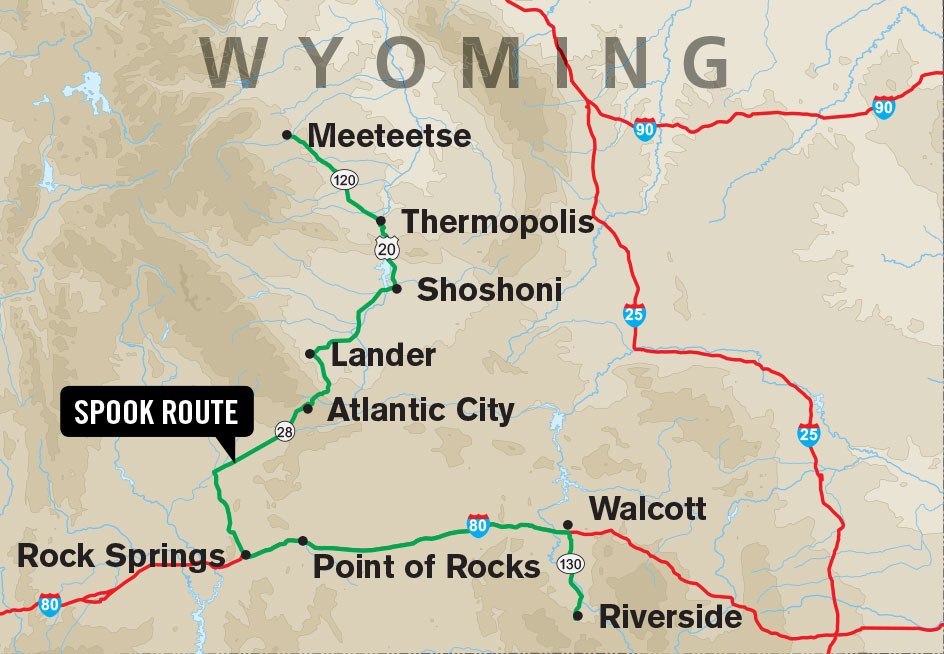

Whether Wyoming’s deserted settlements contain real apparitions from an earlier era is a matter of speculation, but one thing is for sure — wandering around a ghost town is a ticket back in time. The question is, which one to visit? If you’re planning a trip through Wyoming, the following Spook Route, listed north to south, will give you an intriguing peek at the poignant aspects of frontier life.

Kirwin and Double Dee Ranch

Located on the North Fork of the Wood River near Meeteetse, Kirwin had its heyday in the late 19th century when, in 1881, William Kirwin and a hunting buddy discovered gold and silver there. By the late 1890s, the settlement swelled to 200 residents and had 38 buildings, including a hotel, sawmill, post office, stores and numerous private homes. That said, much of the development, including a powerhouse, electric lines and a railroad spur, was abandoned before it was finished. The precious ore turned out to be low grade, then tragedy struck. In 1905, an explosion killed a miner, then two years later, a blizzard dumped more than 50 feet of snow in eight days, causing an avalanche that killed another three people. When the road to Meeteetse became passable again, the entire town departed.

In the 1930s the deserted town became part of the Double Dee Guest Ranch. The dude ranch operated for a decade, through 1942. Amelia Earhart and her husband, George Putnam, were among the ranch’s more famous guests. Earhart started to build a cabin there, but the project was abandoned when she disappeared over the Pacific Ocean.

Today, both Kirwin and the Double Dee Ranch are publicly owned by the USDA Forest Service and are part of Shoshone National Forest. Visitors can see the remains of Earhart’s cabin at the abandoned ranch, then continue to Kirwin where the hotel, several log cabins and mining machinery are scattered around the site.

Plan a full day to visit Kirwin and the Double Dee. A four-wheel-drive vehicle is recommended for crossing one shallow river and several streams to get to the ranch. The Meeteetse Museums complex periodically hosts free tours of the ranch and the ghost town, and can assist in arranging rides or providing directions for self-guided visits.

Meeteetse Museums | www.meeteetsemuseums.org

Atlantic City

Though considered a ghost town, Atlantic City, one of Wyoming’s oldest cities, is an interesting mix of ruins and modern-day rural living. According to the 2010 U.S. Census, 37 people still reside in Atlantic City, which has a reputation as the boom-bust capital of the Cowboy State.

Like many other ghost towns, Atlantic City’s fortunes were directly tied to mining. In 1868, prospectors discovered a vein of gold several feet thick and several thousand feet long. They dubbed it the Atlantic Ledge because of its location on the eastern side of the Continental Divide. Despite the remote mountainous location, 100 miles from the nearest railroad, other hopeful diggers soon came in search of riches, and Atlantic City swelled to 300 people. During the town’s first boom, it boasted a brewery, a beer garden, an opera house and a 90-foot-long dance hall where frontierswoman and guide Calamity Jane is said to have worked.

The city’s second boom occurred in the 1880s when a French engineer and capitalist, Emile Granier, introduced his hydraulic mining system. Granier invested $1,000 and hired 300 Swedish laborers to dig a 20-mile sluiceway to transport gold ore from Christina Lake around the town and then to the south. However, the grade was too steep, causing the water to spill over the sides, along with the gold, which other prospectors were glad to grab. Granier declared bankruptcy in 1893 and returned to France.

The town’s last boom occurred during the Great Depression when miners dredged nearby streams and found small amounts of gold. Some nearby mines reopened, but during World War II, when the U.S. government declared gold a nonstrategic metal, they closed again. Atlantic City was added to Wyoming’s list of ghost towns about 10 years later.

Interestingly, the town experienced yet another boom in the 1960s when U.S. Steel dug a large open-pit iron-ore mine there, but that mine closed as well, in 1982. Three decades later, visitors to this half-deserted hamlet can take a self-guided tour of 27 historic sites, including a mill, barns, cabins, the hotel, a saloon, stores and even a crumbling chicken house amid a handful of inhabited homes and businesses.

Atlantic City Historical Society | www.facebook.com/atlanticcityhistoricalsociety

South Pass City

When prospectors discovered the Cariso Lode in 1868, it triggered a gold rush to South Pass City that attracted more than 2,000 people. The boom turned to bust after only two years, but a number of hardy residents stayed, ever hopeful of another gold strike. The state of Wyoming took over the town on its 100th anniversary, turning it into a state historic site.

Today, South Pass City is among the most well-preserved ghost towns in the western United States. Visitors can walk down the main street of town and step into various shops, public buildings and residences, each curated to show life during the gold rush.

The old dance hall serves as the visitor center and the first stop of the walking tour. The most prominent artifact on display inside the dance hall, an American flag with 44 stars, was hand-sewn in 1890 when Wyoming became the 44th state.

The hotel in the middle of town dates back to 1873 and was originally owned by a widow named Jane Sherlock-Smith. In the 1800s, operating a hotel was one of the few businesses deemed socially acceptable for women. Today, the front desk looks as if Sherlock-Smith could appear at any moment to check in a guest.

The Exchange Saloon is another interesting landmark. Built as a bank during South Pass City’s initial two-year gold boom, the building drew miners to exchange a total of 3,600 ounces of gold dust for minted coins, valued at about $3.85 million today. Pausing there, it’s easy to imagine ordering a whiskey, playing a hand of poker or spinning the roulette wheel after a long day underground. If miners didn’t find gold in the surrounding hills, they could dream of winning riches in the saloon.

The adit (entrance) to Wolverine mine is a short walk above the schoolhouse. Though it never produced a notable amount of gold, it gives visitors a sense of what the mines were like. An ore-stamp mill, a sizable contraption by the adit, crushed mineral-bearing ore, then mercury was added to the pulverized rock to collect the gold particles.

For those who want to dig deeper into the pioneer mining era, a 1.6-mile loop trail follows Willow Creek past several more mine entrances, an arrastra (another type of ore mill), a larger stamp mill and the remains of a brick kiln that is on the edge of South Pass City.

Friends of South Pass | www.southpasscity.com

Point of Rocks

With the start of the American Civil War, the U.S. Army withdrew troops from the west to fight for the Union. As a result, during the 1860s, Indian and outlaw attacks increased along the Oregon Trail, one of the primary east-west routes across the continent, which passed through the middle of Wyoming. The government detoured travelers and mail carriers onto the Overland Trail across the southern part of the territory, believing it a safer route.

More than a dozen buildings preserve the history of the Upper North Platte Valley at the Grand Encampment Museum.

Though not a ghost town per se, the now-deserted stagecoach and Pony Express pit stop at Point of Rocks was one of the more infamous waypoints along the Overland Trail. Known as the Almond Stage Station, it was built in 1862 from local sandstone. Today, visitors can peek out of the window openings in the crumbling stables or into the restored depot. Several plaques retell the history of Point of Rocks, which withstood attacks and attempted arson by various Indians, and was the site of a purported murder.

Jack Slade, a stagecoach driver and notorious alcoholic, killed a passenger named Jules Beni, a Frenchman and one of Slade’s enemies. Several years earlier, Beni shot Slade and left him for dead, but Slade lived, swearing he would one day wear one of Beni’s ears on his watch chain. Slade, a bully prone to whiskey-induced rages, was eventually hanged by vigilantes.

The stage line operated until 1869. With the completion of the transcontinental railroad, passengers and mail gained a more efficient westward mode of transportation. Today, Interstate 80 follows the basic route of the historic Overland Trail.

Grand Encampment

Located between the Sierra Madre mountains and the Snowy Range, Grand Encampment is yet another mining boom town of the late-19th century, though not for gold. In 1897, an English prospector named Ed Haggarty discovered copper, initiating a decade of profitable mining in the area. The Rudefeha Lode (named for the first two letters of Haggarty’s and his partners’ last names) and the Ferris-Haggarty Mine continued to produce copper until 1908.

From the mine, a 16-mile aerial tramway, the longest in the world, carried the ore to a smelter in Grand Encampment, which processed up to 500 tons of ore per day. During the boom, the settlements of Rudefeha, Dillon, Copperton, Rambler, Battle and Elwood sprang up, but they all became ghost towns when the mining company closed after being indicted for selling fraudulent stock and claiming more capital than it owned. During the bust, the town of Grand Encampment quietly dropped “Grand” from its name. Now known simply as Encampment, it has a population of about 400 people.

While not a ghost town in its own right, Encampment hosts many of the buildings from the surrounding ghost towns on the campus of the Grand Encampment Museum. A two-story outhouse, a fire observation tower, a portion of the aerial tram and homes of both prominent and working-class people are among the 19 preserved structures.

Grand Encampment Museum | www.gemuseum.com

TRAVELING THE SPOOK ROUTE

Kirwin to South Pass City

Kirwin to South Pass City

From Meeteetse, south of Cody, travel south 52 miles on State Route 120 to Thermopolis. Take U.S. Route 20 south 32 miles through the Wind River Canyon to Shoshoni. Turn southwest on State Route 789. Go another 55 miles, then head south on State Route 28 past Lander. A series of well-maintained dirt roads with good signage leads to Atlantic City and, 2 miles further south, South Pass City.

Camping: Boysen State Park | wyoparks.state.wy.us

South Pass City to Point of Rocks

Continue south on State Route 28 45 miles to Farson. Take U.S. Route 191 south to Rock Springs. Head east 25 miles on I-80 to Exit 130/Point of Rocks. Turn right (south) off the ramp. Go past the Overland Stage Map, a roadside pullout, then turn left on Sweetwater County Road (no sign). Point of Rocks is 0.1 mile up the hill on the right.

Camping: Sinks Canyon State Park | www.sinkscanyonstatepark.org/visitor/camping

Point of Rocks to Encampment

Take I-80 east 44 miles to Exit 235/Walcott. Go 38 miles on State Route 130 south to Riverside. Turn right (west) on U.S. Route 70. Continue another mile to Encampment. Following the signs to the Grand Encampment Museum, turn left on Sixth Street (dirt), then right to 807 Barnett Avenue.

Camping: Lazy Acres Campground and RV Park | www.lazyacreswyo.com