Indiana’s oldest town is the site of a 79-foot-high memorial dedicated to George Rogers Clark, Conqueror of the Old Northwest Territory, and an interactive museum chronicling the life of entertainer Red Skelton

The pages of history are filled with tales of heroes and their heroic deeds. But sometimes history is kinder to these heroes than their contemporaries had been. Such is the case with surveyor and military leader George Rogers Clark. Nicknamed Conqueror of the Old Northwest Territory and Washington of the West, Clark performed daring feats beyond the Appalachians during the American Revolution that extended the nation’s frontier, winning land from Great Britain that would later become Ohio, Indiana, Illinois, Michigan, Wisconsin and northeastern Minnesota.

Now, schools are named for Clark, statues of him have been erected, and a major bridge over the Ohio River bears his name. Since 1975, when the Indiana General Assembly designated the date, February 25 has been celebrated as George Rogers Clark Day in the state. On that day in 1779, Clark and a small army, after trudging 180 miles across Illinois through frigid floodwater and launching a surprise attack, accepted the surrender of the British occupiers at Fort Sackville at Vincennes, Indiana.

River City

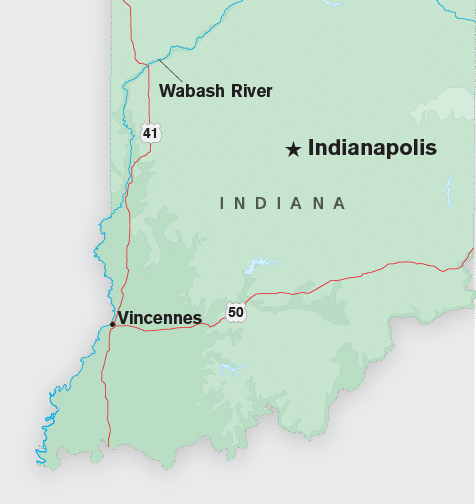

Located in the southwestern part of the state at the junction of U.S. routes 41 and 50, historic Vincennes sits on the lower Wabash River. Vincennes, Indiana’s first city, was under British rule until after the American Revolution and later served as the capital of the Indiana Territory from 1800 to 1813. The more-than-500-mile-long Wabash River forms the southern Indiana-Illinois border. Several U.S. Navy warships are named after the Wabash or the numerous battles that took place on or near the river between the Siege of Fort Sackville and the War of 1812.

That may have been Clark’s most dramatic exploit, but it was just one of many during and after the American Revolution. Despite these feats — actually, because of them — Clark was penniless when the war ended. Just a few years later, he was slandered, disgraced, forced to resign his command and ultimately lived out his days in near poverty, having lost to creditors almost all the land — 150,000 acres — he’d been given for service in the war.

As the highest-ranking officer in the territory during the war-time campaigns, Clark had been responsible for obtaining supplies for his troops. And though he had no official support, he signed for the materials, believing that after the war ended, the government, considering his accomplishments, would assume the debt.

But that didn’t happen, at least not during his lifetime.

He attempted to recoup his losses with work as an Indian commissioner and surveyor, but was unsuccessful, and for the rest of his life he was plagued by claims and suits related to the war debts. Clark was in the care of his sister, Lucy Croghan, on her farm near Louisville, Kentucky, at his death, in 1818 at age 65, following a couple of strokes and the loss of a leg. His family then took up the cause and eventually obtained a settlement.

His accomplishments may have been dismissed during his lifetime, but the role he played in American expansion is now long recognized. In 1928, President Calvin Coolidge ordered a memorial be built to the forgotten hero.

George Rogers Clark National Historical Park was created in Vincennes. In 1933 (the 150th anniversary of the Treaty of Paris, which ended the American Revolution), the classical Greek-style memorial to Clark was dedicated. It stands on the banks of the Wabash River where old Fort Sackville is believed to have been.

Fur trader Francis Vigo, Clark’s spy in Vincennes, traveled to Kaskaskia to inform Clark that Fort Sackville was undermanned and vulnerable. Vigo also participated in the founding of Vincennes University.

The massive round memorial, gleaming white granite 79 feet tall and ringed by 16 towering fluted columns, is so grand that at first glance you might think you’ve made a wrong turn and somehow gotten to Washington, D.C., where similar monuments dot the landscape.

The interior, of Indiana limestone and Italian, French and Tennessee marble, is no less grand. A 7½-foot bronze statue of a confident-looking Clark stands in the center of the room, and seven 28-foot-tall murals depicting his role in developing the land west of the Appalachians decorate the circular wall. The nearby visitor center, with a 30-minute film, brochures, maps and dozens of exhibits, provides a comprehensive account.

Born in Virginia, Clark was a “magnetic leader, persuasive orator and master of psychological warfare,” according to the National Park Service. But in 1772 at age 20, like many others in search of new land to settle, he crossed the Appalachians into Kentucky, which was still part of Virginia, to live in the Ohio River Valley. This meant defying the British “proclamation line” of 1763, which dictated that American colonists could live only east of the mountains.

By 1777, with the Revolution under way in the East, the British at Fort Detroit were sending out Indian war parties to destroy American settlements in the west. Clark, one of Kentucky’s military leaders, convinced Governor Patrick Henry to let him take the war to British-controlled posts of French inhabitants north of the Ohio River, with the ultimate goal of capturing Fort Detroit, where the British were based.

The elegant Basilica of St. Francis Xavier, also known as the Old Cathedral, was built in 1826 and is the fourth church on the site. It is located opposite George Rogers Clark National Historical Park.

On Independence Day in 1778, Clark and a small army of patriots took Kaskaskia without firing a shot, and subsequently Cahokia, both in Illinois country. Then, at the urging of Father Pierre Gibault, vicar general of the Territory of Illinois, the people of Vincennes on the Wabash also swore allegiance to the patriots.

When the news reached the British at Fort Detroit, Lieutenant Governor Henry Hamilton and a small army headed south for Vincennes and were joined along the way by hundreds of Indians still loyal to the British. The size of the force convinced those at Vincennes to renounce their allegiance with the United States, and once again Fort Sackville was in British hands.

But in early 1779, Clark learned that Hamilton had sent most of the Indians and French militia home for the winter, and while still in Kaskaskia, he assembled 170 Virginians and Illinois French volunteers, and set out on the daunting trek across Illinois’ “drowned country.” For 10 days they waded through sometimes-shoulder-deep floodwater and reached Fort Sackville on February 23.

Visitors admire the heroic statue of George Rogers Clark inside his memorial.

The British held on till Clark threatened to storm the fort and give no quarter, then agreed to the surrender, which was formalized on February 25. The Union Jack would never again fly over Fort Sackville, but with reinforcements unavailable, Clark was unable to proceed to his ultimate goal, Fort Detroit.

When the Treaty of Paris ended the Revolution in 1783, Britain ceded the Old Northwest Territory to the United States, and due in large part to Clark’s war-time efforts, the size of the country was nearly doubled. But Indian raids on American settlements continued. In 1786 Clark led an expedition against villages along the Wabash, but before victory could be won, supplies ran low, and his 300 men mutinied. Then, rumors spread that he had often been drunk on duty.

Joe Herron, chief of interpretation at the park, explained that this may just have been jealous slander, but no inquiry was ever held. Nonetheless, Clark, by this time a brigadier general, was forced to resign. With the opening of George Rogers Clark National Historical Park, the hero whose history had been largely ignored for nearly a century and a half finally got his long-deserved recognition.

Vincennes, which had been founded by French fur traders in 1732, became Indiana’s territorial capital on July 4, 1800, and served until the capital was moved to Corydon in 1813. Indiana became a state three years later, and in 1825 the capital was moved

to Indianapolis.

But the original Indiana Territorial Capitol remains and can be toured, along with several other historic structures located a dozen blocks east of the national historical park. Walking tours, led the day of our visit by Program Director John Mays, begin at the visitor center, a replica of an 1850’s log cabin (1 W. Harrison Street), where books, maps and brochures are available. The well-preserved capitol, a plain two-story clapboard structure painted ruby red, is furnished with benches and chairs, as it would have been more than two centuries ago.

The boyhood home of comedian and favorite son Richard “Red” Skelton.

The complex also includes Jefferson Academy, Indiana’s first public school, founded in 1801. Mays explained that girls as well as boys, ages eight to 14 or 15, attended the school, which was taught in French, Latin and English. In 1806, it was incorporated as Vincennes University, one of only two colleges in the country founded by a U.S. president (in this case a future president, William Henry Harrison; the other is the University of Virginia, founded by Thomas Jefferson). Also at the complex is a replica of the Elihu Stout Print Shop, the territory’s first newspaper, the Indiana Gazette, established in 1804.

Harrison’s home, Grouseland (3 W. Scott Street), is nearby. Harrison was governor of the Territory of Indiana from 1803 to 1812, and elected ninth president of the United States in 1840. Completed in 1804 and designated a national historic landmark in 1961, the elegant Georgian/Federal-style mansion is now a museum and open for guided tours.

Other historical attractions include Old French House (509 N. First Street), a French Creole-style building that was built in 1809 and home to French fur trader Michael Brouillet. Furnishings are typical of the early 19th century.

The collection of artifacts at the Indiana Military Museum (715 S. Sixth Street) is considered one of the best in the Midwest. The 6,500-square-foot museum, with exhibits indoors and out, displays vintage vehicles, weaponry and uniforms from every major American conflict, Civil War through Desert Storm.

Loveliest of the town’s historic buildings is the Old Cathedral (Basilica of St. Francis Xavier, 205 Church Street), a short, grassy stroll from the Clark monument. The Greek Revival-style cathedral, the fourth church to stand on the site (the first was built around 1748), dates from 1826. A statue of Father Gibault, Patriot Priest of the Old Northwest, stands in front.

Inside, the basilica is lavish with exquisite paintings, Doric columns that are yellow poplar trees plastered and painted to resemble marble, and vibrantly hued stained-glass windows that were installed in 1908. Across the courtyard from the church is the oldest library in Indiana, containing some 10,000 rare volumes, some of which date to the 14th century.

For another look at early-American history, drive 3 miles northeast of town on Lower Fort Knox Road to Fort Knox II, near Ouabache Trails Campground, where we stayed.

The second of three Fort Knox locations that protected the city from Indian attack has a fence of short logs where the palisade once stood.

The U.S. Army had built Fort Knox I in Vincennes in 1787. It was moved to the present site in 1803, becoming Fort Knox II, with a stockade and blockhouse, store and powder magazine. The old fort, on a level plain high over the chocolate Wabash River (Ouabache in French), is no longer there, but its outline is marked in the grass with short posts. On 13 bronze placards, visitors read about the history of the area, such as the trouble between settlers and Indians, and Harrison’s 1811 victory at the Battle of Tippecanoe, which later prompted the slogan “Tippecanoe and Tyler Too” that swept him into the presidency.

Secretary of War William Eustis removed the garrison from Fort Knox II in 1812, and its timbers were floated downriver to be reassembled in Vincennes as Fort Knox III. Five years later, that facility would be dismantled, as struggles between Indians and European culture east of the Mississippi had come to an end.

For our last stop in town, we turned from serious history to the whimsical — the Red Skelton Museum of American Comedy (20 Red Skelton Boulevard). Clown, comedian, actor and mime Richard “Red” Skelton was born in Vincennes in 1913. The museum, which opened on the anniversary of his 100th birthday, is a wealth of exhibits, many of them interactive, that chronicle his life and 70-year career as an entertainer.

Although Skelton is best known as a “clown,” a term he preferred to “comic,” because a “clown uses pathos,” he was also a prolific writer of short stories and music (some 8,000 songs), and enjoyed a second career as a talented painter. Visitors watch amusing clips of him as Freddie the Freeloader, Clem Kadiddlehopper and others, and learn about his commitment to public service, and that all was not laughter in Skelton’s personal life (he was divorced twice; his son died of leukemia at age nine).

There’s also a gallery of his artwork. Most of the paintings are of clowns, but that’s not surprising. Skelton said, “A clown is a warrior who fights gloom.” He believed his purpose in life was “to make people laugh.”

Where to Stay

Beautiful Ouabache Trails State Park has an excellent campground just 2 miles north of the city. (Right) Visitors admire the heroic statue of George Rogers Clark inside his memorial.

We recommend the county-owned campground at Ouabache Trails Park, which includes 35 RV sites, all with water, electricity, picnic tables and fire rings. The pet-friendly campground offers showers and laundry facilities. A dump station, firewood and ice are available. Quabache Trails Campground is open from April 1 through the first weekend in November.

812-882-4316 | www.knoxcountyparks.com

For More Information

Vincennes/Knox County Visitors and Tourism Bureau

800-886-6443 | www.visitvincennes.org