With dramatic coastlines, soaring mountains and extravagant wildlife, the ultimate road trip takes RVers into the heart of North America’s Last Frontier

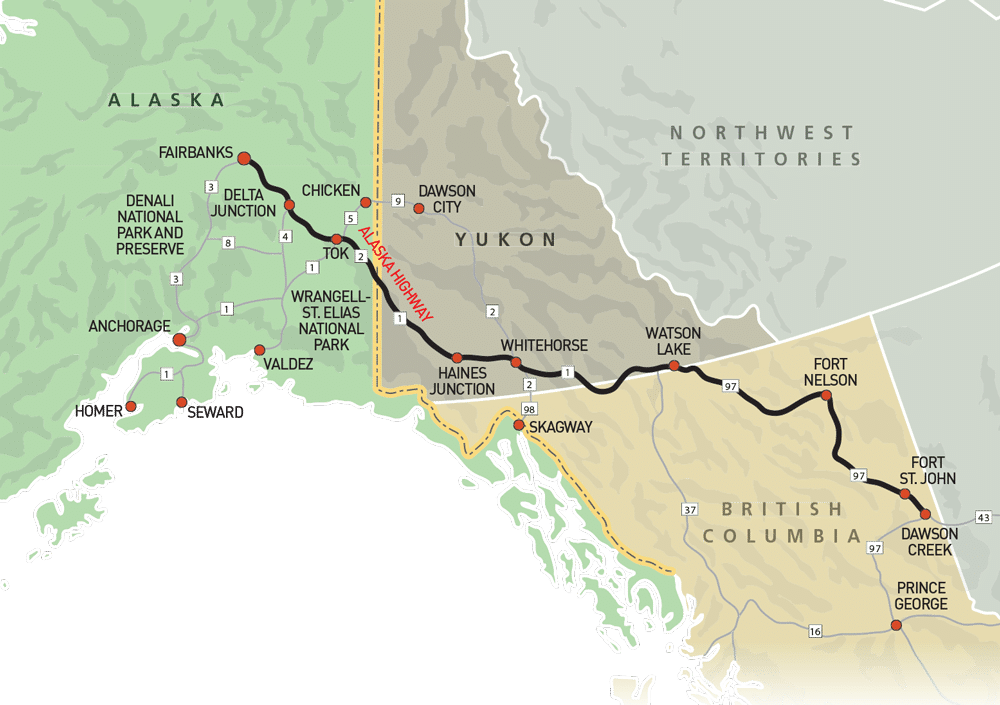

In Alaska Odyssey, Part I, I discussed the first leg of our journey, starting in Prince George, British Columbia,  and traveling about 1,700 miles to Denali National Park and Preserve via the Stewart-Cassiar, Alaska and George Parks highways, with detours up the Klondike and Top of the World highways. Part II follows our route to the Kenai Peninsula, Valdez, Wrangell-St. Elias National Park and Preserve, Skagway and back home.

and traveling about 1,700 miles to Denali National Park and Preserve via the Stewart-Cassiar, Alaska and George Parks highways, with detours up the Klondike and Top of the World highways. Part II follows our route to the Kenai Peninsula, Valdez, Wrangell-St. Elias National Park and Preserve, Skagway and back home.

Hooked on Alaska: Of the more than 12,000 rivers in the Last Frontier, none is more popular for fishing than the Kenai.

Kenai Peninsula

The first 110 miles of the Sterling Highway (Alaska 1) en route to the Kenai Peninsula are about as pretty a drive as you can experience. With water on one side and mountains on the other, and Portage Glacier posing for a portrait, we’re enthralled. We’re headed to Homer, the self-styled Halibut Fishing Capital of the World.

Homer was established in 1895 and has a fun, funky vibe that attracts artists and other creative types. The town is divided in two, with a 4.3-mile spit protruding into Kachemak Bay and a traditional downtown where you go to buy groceries. The spit is where the action is. The restaurants are without pretension, the shops don’t scream “tourist,” and the angler has a multitude of charter-boat choices.

Our experience was significantly influenced by a chance encounter. While having coffee and a nosh on the deck at a local bakery, a chat with our neighbor led to an invitation to their home for dinner and a chance to join them the next day on their boat for a trip to nearby Halibut Cove, a charming landlocked village a few miles across the bay. Cheers, Larry and Petja!

Camping options on the Homer spit are plentiful, and all of them have the benefit of proximity to the bay. Most of the campgrounds are functional and a bit funky, an ambience that fits with the rest of the town. Dry campers have access to two municipal campgrounds perched on the bay. Boondockers will find Homer pretty liberal about where you camp, and you see tents and RVs scattered along the beach.

When the salmon are running, bears can often be seen near the Solomon Gulch Fish Hatchery, the largest salmon hatchery on Prince William Sound.

Or you can do as we did the first two nights and camp at the upscale Heritage RV Park and partake of the round-the clock espresso bar. The rest of our stay was spent at the more modest Homer Spit Campground, not for financial reasons but because it fit better with what Homer seemed to demand and was within easy walking distance of most of the places we wanted to visit.

I like unique knives and my wife, Mara, likes jewelry. Homer is a good place to look, as many craftspeople sell their wares here. I noticed that much of what we saw claimed to be made of exotic materials, particularly ivory from the woolly mammoth. Suspecting a scam, I learned that in Alaska ivory from extinct animals is legal to sell. Further research disclosed that ivory and bones were uncovered as by-products of mining and of native people excavating in their traditional home sites, as well as on lands uncovered by retreating glaciers, covered with ice for millennia.

With two people and limited refrigeration, fishing charters were out, so we focused on the educational. Homer’s Pratt Museum and the Alaska Islands and Ocean Visitor Center both offer insights into life on the bay.

Located on the south shore of Kachemak Bay, the landlocked village of Seldovia got its name from the Russian word seldevoy, meaning “herring bay.”

Field-tested tips from locals are always welcome, and Larry and Petja shared these with us. Best conventional seafood dinner: Captain Pattie’s, where they will also cook your fresh-caught fish. Best breakfast: La Baleine Café, with meals for the hearty eater. Best place to drink: Salty Dawg Saloon, with the right mix of locals and visitors so you feel right at home. Best bakery: Two Sisters, downtown.

As promised, Larry and Petja pick us up for the 7-mile voyage to Halibut Cove, founded in 1880. Early this century, it had a population of 1,000 and housed 42 herring salteries where the fish were processed. Today, it is largely a day-trip destination to the island’s lone restaurant, the Saltry. Try the seafood chowder or the seafood combination plate. There are no roads, but hikers can navigate the boardwalks and trails that populate the island. Bird-watching and kayaking are popular pursuits. Halibut Cove is home to one of America’s few floating post offices.

Compared to Halibut Cove, the village of Seldovia is a metropolis. Also reached by boat, it has a road and four restaurants. The road is only 12 miles long and doesn’t connect to other communities on the peninsula, but so what? Like Halibut Cove, it’s best thought of as a day trip or weekend getaway. We walk around its boardwalks and gravel streets in utter quiet; a poet would feel at home here, and a few probably do. We enjoy the Seldovia Village Tribe Museum and the St. Nicholas Russian Orthodox Church, perched on a bluff overlooking the town and serving parishioners since 1891.

|

An interesting side note: Cook Inlet, the waterway that borders Homer and runs along the west side of the peninsula, branches into Turnagain Arm, which has the fourth highest tidal range in the world. Tidal fluctuations in Cook Inlet are not as extreme but can exceed 25 feet. If you are playing or camping on the shoreline, be aware of your circumstances.

Seward beckons, home to Kenai Fjords National Park. To get there from Homer, backtrack north on the Sterling Highway to the intersection with the Seward Highway (Alaska 9) and drive south until it ends. Where Homer is open, Seward is nestled on Resurrection Bay between mountain ranges and has a different feel. It was the original southern terminus of the Iditarod Trail, established in 1910 as a mail route between Seward and Nome, and later made famous by the sled-dog race that bears its name. The southern terminus was later relocated to Anchorage.

Kenai Fjords National Park is mostly water and mountains, and is best explored by boat. The National Park Service works closely with private charter operators who will take you out and entertain you with wildlife and fjord viewing. The 8.2-mile-roundtrip Harding Icefield Trail and shorter hikes to Exit Glacier provide options for people who would rather walk.

Camping here is a pleasure. The municipal Waterfront Park on the outskirts of town has five campground locations. We stay in the Resurrection section, right on the bay, with electric and water hookups.

Valdez

Leaving Seward, we prepare for the drive to Valdez and our last days on the coast before heading inland. To get there, we take the Glenn Highway (a different stretch of Alaska 1) to the junction with the Richardson Highway (Alaska 4), and then south to Valdez.

I have always had this dream of finding the perfect campsite. It would be situated on a quiet, pristine lake. There might be a trout or two splashing about. The area would be beautiful, with nobody else in sight. Would I ever find it? Not until now. Based on a tip, we stop at Blueberry Lake State Recreation Site, 30 miles outside Valdez, and find campsite number 7 vacant. Without a word, we park and self-register. Mara collects wild blueberries to enliven our morning flapjacks, and I catch and release my trout.

The Kennecott copper mine operated from 1911 until 1938 and is now part of Wrangell-St. Elias National Park and Preserve.

A couple of days later, entering Valdez, we come upon Dayville Road, leading to the Solomon Gulch Fish Hatchery. Where there are fish, there are bears, and since the salmon are migrating, we think we might chance upon a hungry one. Sure enough, as we approach the hatchery, mother black bear is teaching her three cubs to fish.

Most of us know the salmon life cycle: born in freshwater, migrate to the sea, and return to spawn and die at their place of birth. At the hatchery, we witness thousands of fish fulfilling their destiny, preyed upon by voracious gulls, a pod of pinnipeds and anglers after an easy catch, a disconcerting sight. One would wish a more dignified end to their lives.

Nestled in the Chugach Mountains and bordered by Prince William Sound, Valdez has been called Alaska’s Little Switzerland. It was established in 1897 as a port of entry for prospectors hoping to strike it rich in the Klondike Gold Rush. From the picturesque harbor, one can board a boat to fish, visit the Columbia Glacier or view wildlife in Prince William Sound. Sea kayak rentals are a thriving business.

Valdez has quite a history. Not only is it the southern terminus of one of the world’s largest crude-oil conduits, the Trans-Alaska Pipeline, it was near the epicenter of the 1964 Great Alaska Earthquake, the second most powerful ever recorded, and the closest city to the 1989 Exxon Valdez oil spill, the largest in U.S. waters before the 2010 Deepwater Horizon spill. All of this we explore in the Valdez Museum and Historical Archive.

Wrangell-St. Elias

At 13.2 million acres, Wrangell-St. Elias National Park and Preserve is the largest in the national park system. Nine of the 16 highest peaks in the United States ascend from here. The park has the highest concentration of glaciers in North America, and the only access routes are two horrible gravel roads.

Why, you might ask, would we want to visit a huge place with limited vehicle access? Because this is the “real Alaska” — wild, undeveloped and populated by folks who don’t live like the rest of us, and don’t want to. Its millions of acres of land are rarely if ever touched by humans. Hike a few miles off any road, and what you get is pure wilderness.

After backtracking on the Richardson Highway from Valdez, we head east on the Edgerton Highway (Alaska 10). The Edgerton is paved to the village of Chitina (pronounced Chit-na), where it becomes the McCarthy Road. After a few miles, we discover that this drive will vie for the Worst Road in Alaska. We backtrack to a primitive campground and set up for the night. A hand-printed sign near the toilet warns us that fresh grizzly scat has been spotted nearby.

In the morning, I introduce myself to Ranger Earl. Mentioning my experience on the road, I inquire about the condition further on. He notes that the part we drove was the good part. We’re headed to McCarthy, and he advises us of a shuttle service that will take us the 60 miles. Comparing the cost of the shuttle (about $100 per person) with the cost of new tires and a suspension system, we decide to wimp out and take the shuttle. As a bonus, our dog can come, too.

The hamlet of McCarthy and this road exist because of copper, discovered near the Kennicott Glacier. Five miles away, the abandoned mining camp of Kennecott (a misspelling that stuck) operated from 1911 until 1938. McCarthy grew up to house and entertain mine employees, and we intend to see it and the mine.

Our driver is Annika. She and her pal Eva pick us up the next morning at 8 sharp at Kenny Lake RV Park. Our coconspirators are a young couple from San Francisco undertaking a 10-day backpacking trip and three ladies from the Midwest looking for an antidote to cruise ships.

Annika, Eva and another driver who handled the return trip live here but are not native Alaskans; all came to visit and never left. They are intelligent and seemingly happy, a couple of divorces notwithstanding. None have running water or inside plumbing in their homes. They carry water from a stream or village well in 5-gallon buckets. A nice outhouse, or one with multiple seats, is a source of domestic pride, like a Mercedes in the driveway. All are at home with guns and use them to gather food and for protection.

|

Eva told us funny bear stories based on the theme of “Guess Who’s Coming to Dinner.” Here you have a group of people who live in a way that some would consider primitive but do so by choice. You can tell from their body language that they feel sorry for us flatlanders who sacrifice the opportunity to live in this majestic place for creature comforts and material things.

McCarthy (population 50) hasn’t changed much since its mining days: no central water supply, no sewer or electricity, no medical facilities and no school. The now-abandoned mine is owned and managed by the National Park Service. Private concessions offer experiences like ice-climbing.

On a roll, we decide to check out the only other road into the park, the Nabesna Road. From Chitina, we backtrack to the Richardson Highway and take it north to the Tok Cutoff. The village of Slana is the site of another ranger station and the road to the old Nabesna gold mine, now off-limits.

We learn that, of the 42 miles of road, the first 16 are paved and the next 12 are dirt and navigable by medium-size RVs. Twenty-eight miles sounds about right, getting us to our goal of Kendesnii, Wrangell-St. Elias’ only National Park Service campground, with pit toilets and much solitude. The 10 sites are full when we get to the campground, so we set up at a pull-off (this is allowed here) and let a flock of trumpeter swans serenade us. Not bad.

Camping here caused me to reflect on what Alaska travel is about. You will see majestic mountains, and after a while, another one just becomes another one. So it isn’t about viewing mountains or glaciers with names but experiencing the vastness of the place and the people who have chosen to live here.

Connecting Valdez to Fairbanks, the Richardson Highway ribbons around the Chugach Mountains and the Alaska Range.

Skagway

Since we need to pass through Whitehorse again, we make the 100-mile detour to Skagway. We return to Tok and then head south on the Alaska Highway toward Whitehorse. The road is brutal for 90 miles. We come to the tiny Yukon town of Burwash Landing and marvel at the quality of the exhibits at the Kluane Museum of Natural History.

I call Skagway the Un-Alaska. It was a very important player during the Klondike Gold Rush and by late 1897 had a population of 20,000. The boom led to bust within two years, and soon Skagway’s population was 500, but it survived to fight another day.

Period buildings remain, but the town exists to serve cruise ships — two and sometimes three were in port during our stay. Jewelry stores line both sides of the street and outnumber other types of businesses, even T-shirt shops. One salesman greeted me in a mink coat. Alaska cruises have their place, and the Inside Passage is undeniably beautiful, but Skagway isn’t part of the real Alaska anymore.

Conclusion

One of the reasons many of us go camping is to get away from it all for a time. There is no place in North America and few places in the world where you can do that on this scale on (mostly) roads suitable for RVs.

Our trek started in the San Francisco Bay Area and ended in the same place, 9,500 miles later. More than 5,700 of those miles were in Canada and Alaska, and we spent $2,200 on gas. All in all, a bargain.

This is more a journey than a road trip. It’s not a place to set up cruise control and count the miles from point A to B. You will be motivated to drive as slowly as traffic will allow, gazing to the left, then to the right. Mountains and glaciers announce themselves with some warning; bears, caribou and other critters do not, and you don’t want to miss them.

Every swamp looks like moose habitat. Every white speck on a distant peak may be a mountain goat. Bears will be inspected for the telltale hump that defines a grizzly, somehow more important than a mere black bear. Tiny towns have world-class museums, and you don’t want to miss those, either.

Many RVers have the Alaska Highway on their bucket list. My advice is to empty that bucket as soon as possible.