I called up Dean Oswald last February from California. He and his wife Jewel had just returned from an 11-day train trip across the West. Since their primary interest is bears, they got off the train in Seattle for a couple days at the zoo.

In Arizona, they left the train again in Flagstaff. Dean has friends there who have a new place near Williams that’s called Bearizona — a drive-through, wildlife park. It has a 21⁄2-mile drive that covers 160 acres of fenced-in forest where black bears, wolves, bison and other animals roam about.

I met Dean last summer when I was in Michigan’s Upper Peninsula. He has 80 acres north of Newberry, just off Highway 123. It’s 20 minutes south of Tahquamenon Falls, a popular spot with tourists exploring the remote, northern reaches of Michigan.

Increasingly, tourists also stop by to see the 29 black bears at Dean’s ranch for rescued bears.

About 25 years ago, Dean was going to get a dog, but decided on a bear instead. “Unfortunately, bears are like kids, once you get one, then you want some more,” Dean says. And as their numbers grew, so did the visitors who came to see them. So 12 years ago, to help pay for the ferocious appetites of the bears, he started charging by the car — $15. People stay as long as they want. The bears are behind a fence.

“These bears get a lot of meat, good meat,” he said. “I buy corn by the ton and grow rye. I get food from restaurants. The bears love it. In fact, they eat better than you and I do.”

He spends 50 hours a week tending the bears, assisted by his family that includes two young grandchildren.

On the phone, I was reminded how Dean’s voice sounds like its coming out of a deep canyon. His enunciation is flawless, but with a phonic shading, so that you know that he was raised somewhere between Fargo and Sault Ste. Marie.

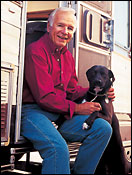

He is 70, but looks 50. His white hair is cut short like that of a marine, which he was once. He was also a prizefighter, a policeman and a fireman and could still be a recruiting poster for any one of the organizations.

Dean and Jewel don’t get to travel in the summer when most of us do. Their schedule is determined by nature — the hibernation timetable of the black bear.

“They start going to sleep in September,” Dean said. “We don’t see them again until mid-March.” Before going into hibernation, a bear can put on 30 pounds in a week. In hibernation, its metabolic rate is cut in half; its body temperature averages about 88˚ F. The heart rate of a hibernating bear has been measured as low as eight beats per minute.

During hibernation — usually January — is when cubs are born. After the in-den delivery, the mother and cubs sleep out the rest of the winter together.

Dean points out that it’s illegal in Michigan to buy or breed bears. Still, he is never short of cubs.

“We took in two last year. And we already had five. I get calls from all over the country. Mother bears get killed. If the only options are that they euthanize the cubs or I take them … well, you know how it turns out.

“We bottle-feed the cubs every three hours. They learn quickly that when the light’s off at night, the formula mill shuts down ’til morning. They stay right in the house with us for about two months. The bond that develops is permanent.”

Welcome to America’s Outback.

……….

Bill’s e-mail address: [email protected]. Next month Bill will be in Woolaroc, Oklahoma.