It’s been two decades since game seekers started prowling for tiny trinkets and hidden scrolls with GPS-aided geocaching. Today, anyone with a smartphone can get into the sport

“Let’s go for a walk.” Those words send dogs into a frenzy. The kids? Not so much. That’s problematic when the point of camping is to get outside and escape the man-made cubes that confine us.

All campers, from the minimalist backcountry tenter to the luxury-cottage-on-wheels RVer, agree that few things in life rival sitting around a flickering campfire and snacking on s’mores beneath the speckled gaze of a billion alien worlds. It’s a balm for our urbanized souls. But when the sun is high, it’s physical activity that does us good.

For families with kids, getting active at the campground typically comes in three flavors: bicycles, water and playgrounds. During daylight hours, campgrounds are alive with the bustle of children racing around on their two-wheelers, making a splash at the beach or pool, and swinging, swaying and sliding on various playground structures.

When the little ones are little, we big ones tend to supervise, often moving only to save a toddler darting toward danger. As they age, our supervisory duties lessen, leaving us with limited responsibility beyond holding down lawn chairs.

The author’s children, Sophie and Jake, explore the treasures in newly found caches at Alberta’s Peter Lougheed Provincial Park (left) and McLean Creek Provincial Recreation Area (right). Photos: Jamie Schmidt

Burning excess calories accumulated during those nightly campfires necessitates getting ourselves moving. Some folks may indulge in a couple hours of spirited field sports or a lengthy cycle excursion, but Mom and Dad often prefer a simple walk. And, unlike your canine, kids greet such ambitions with groans of disinterest.

Our solution to this fitness predicament is geocaching, a delightfully simple GPS treasure-hunt game that harks back to orienteering and can be played just about anywhere. Who knew the lure of hidden trinkets could turn a boring walk into hours of rewarding outdoor family time?

Twenty Years of Treasure Hunting

The first documented geocache was placed by Dave Ulmer in a wooded area near his Beavercreek, Oregon, home on May 3, 2000, one day after the U.S. military, by executive order of President Bill Clinton, removed Selective Availability (SA) from the Global Positioning System (GPS).

SA was an intentional error added to public GPS signals to distort locations by up to 100 meters (328 feet) horizontally and/or vertically. Generated by cryptographic algorithms exclusively available to authorized users such as the U.S. military, SA’s purpose was to prevent enemies from using commercial GPS receivers in guided weapons.

By the 1990s, however, pressure was mounting to remove SA from GPS. Differential GPS, a system of fixed stations with accurately established positions such as the Coast Guard’s low-frequency (LF) beacons, could calculate the SA error and transmit corrections to GPS receivers, rendering SA all but irrelevant.

Top: A tribute plaque in Estacada, Oregon, commemorates the first ever “stash,” hidden on May 3, 2000 (photo: Groundspeak). Above: A plaque at Nova Scotia’s Graves Island Provincial Park marks the site of Canada’s first geocache.

On May 1, 2000, the SA error was set to zero for public signals after the military had developed a means of disabling GPS in conflict areas without affecting its own forces or the remainder of the globe. Two days later, Dave Ulmer changed the face of outdoor entertainment with his hidden bucket of booty.

Ulmer’s geocache, originally called a “stash,” consisted of a partially buried plastic bucket filled with software, videos, books, money, a can of beans and a slingshot. He published coordinates on a Usenet newsgroup, and within three days it had been found twice.

The first to do so was Mike Teague, who soon after placed two stashes of his own on Mount St. Helens and began cataloging stashes on his GPS Stash Hunt web page. That summer, stashes were renamed “geocaches” because of concerns about negative connotations associated with the former name, and Seattle web developer Jeremy Irish registered the www.geocaching.com domain. Teague announced that Irish’s website would become the home for all his listings, lighting the fuse to a future fad.

Finders, Keepers

Our first exposure to geocaching came courtesy of a visiting cousin. It was the summer of 2011, about the time geocaching reached peak hype. He possessed a new gadget, a GPS device, and he couldn’t wait to show us what it could do. With it, he took us on a treasure hunt to find a geocache that was supposedly hidden near our house.

My initial response was skeptical. I was suspicious of my cousin’s claim, especially the purported pleasure such an activity would bring us. I relented, as a good host does, and we set about finding the geocache with my wife and children.

We walked along a grassy berm at the edge of our neighborhood toward some small spruce trees where locals had beaten a dirt path down to a bus stop. The GPS guided us toward one spruce in particular.

SA may have been deactivated in 2000, but GPS is not flawless. Everything from atmospheric conditions to special relativity affects its accuracy. It’ll get you close to the cache, within a yard or so, but it won’t stick your nose straight into it.

Checking their GPS device at Ya Ha Tinda Ranch near Banff, Alberta, Jake and his mom, Stephanie, determine which direction to take in their hunt for a hidden geocache.

All five of us set to searching. After several minutes of growing bewilderment, we finally succeeded. Much to my daughter’s delight, we found a plastic film canister affixed to a branch a couple of feet off the ground — a micro cache.

Inside the film canister was a logbook filled with dates and names of people who had previously found this geocache. We added ours, returned the canister to its hiding spot, and took a moment to relish our success. Which is to say, the others gleefully chatted about the experience while I stood silently thinking to myself, “Seriously?”

Despite the inauspicious start, for me at least, geocaching has since become a mainstay of our camping adventures. By 2014, we had purchased our own GPS device and were dutifully downloading coordinates to caches near our campsites from www.geocaching.com.

On an urban treasure hunt, the kids discover a magnetic-keybox cache hidden under a railing at a parking garage.

That’s the aforementioned website Jeremy Irish created back in 2000 along with cofounders Elias Alvord and Bryan Roth. The three worked at a dot-com startup, and the fledgling website was little more than a hobby. But as geocaching grew in popularity, their side venture evolved into a full-fledged, not to mention full-time, business.

Incorporating as Groundspeak and raising capital through the sale of geocaching T-shirts, the website evolved into a profitable Seattle-based company with more than 70 employees and its own visitor center. Now known as Geocaching HQ, the de facto headquarters of geocaching lists more than 3 million active geocaches in 191 countries on all seven continents.

We’ve found 66 of them, mostly traditional caches. They’re the most common, ranging in size from micros, like our first find, which contain only a paper log, to large, treasure-laden containers.

Large caches are rarer, being much more difficult to hide well. The traditional caches we typically find vary in size from film canisters to common Tupperware lunch containers. The largest we’ve found are ammo cases that offer plenty of room for a logbook, writing utensil and an assortment of riches.

Most geocaches range in size from micros that hold only a log (left) to treasure-filled canisters with tradable trinkets (right).

Search and Replace

Any geocache containing a treasure is sure to excite the kids, but geocaching is also an honor-bound hobby. For every trinket you take, you are expected to leave one in return. As a result, our backpack contains an assortment of baubles each time we head out on a hunt. Those loot bags my kids bring home from birthday parties are filled with ideal items to leave, though we’ve certainly found a wide array of unique to ridiculous things over the years.

We’ve also become more discerning about the geocaches we choose to seek. All caches on www.geocaching.com include a description, the size of the container and logs from those who’ve previously found it. Difficulty to Find and Difficulty of Terrain are also rated on a scale from one to five. This allows us to choose geocaches that best suit our kids’ ages and ability, not to mention our eagerness on any given day.

And those logs, while helpful in finding geocaches we are struggling to locate, are also integral to the social aspect of geocaching. Players are encouraged to thank cache owners and elaborate on their experiences in finding them. A litany of unique acronyms and jargon such as TFTC (thanks for the cache) has evolved alongside the game (see “Common Geocaching Terms” below). This covert communication also enables geocache owners to monitor the condition and popularity of their hides.

Author Jamie Schmidt discovers a cache attached to a tree branch at Alberta’s Peter Lougheed Provincial Park.

My personal favorite is the adoption of “muggles” from the Harry Potter books to describe non-geocachers. Geocache code urges cachers to prevent muggles from accidentally discovering hides or clue in to what we are up to.

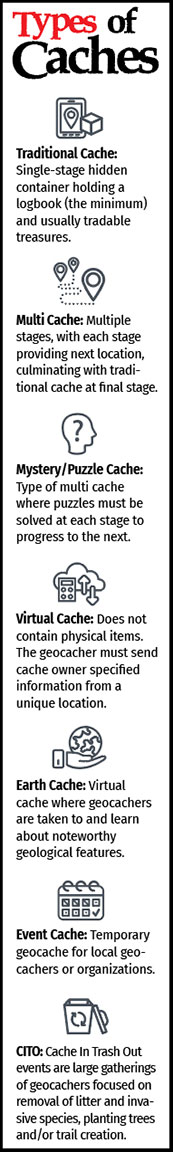

Traditional geocaches are not the only kind available. As geocaching exploded in popularity, so did the variety of cache types (see “Types of Caches” below). Being geologists, my wife and I are particularly fond of earth caches.

Rather than unearthing manufactured treasures, earth caches facilitate the discovery of Earth’s treasures. Geocachers are taken to singular geological features where educational notes teach them about the processes that shape our planet. This is a terrific way to see spectacular scenery, and it never hurts to slip a little schooling into summer holidays.

Virtual and webcam caches, where geocachers are directed to out-of-the-ordinary locations, became so popular that they have been spun off into their own GPS game, “waymarking,” with a dedicated website operated by the Groundspeak folks.

Left: Sophie and Jake review a map on their GPS device. Right: Jake points out a hidden cache behind a road sign.

Cache Advance

Recently, we decided to play the other side of the game and tried hiding our own geocache. Our first attempt was in a green space near our home, a location quickly rebuked as too close to an existing geocache.

An army of volunteers helps Groundspeak confirm, rate and allow or refuse each geocache. These avid hobbyists help keep the game functioning while maintaining good relations with local authorities whose acceptance of geocaching varies.

An army of volunteers helps Groundspeak confirm, rate and allow or refuse each geocache. These avid hobbyists help keep the game functioning while maintaining good relations with local authorities whose acceptance of geocaching varies.

Our second attempt was in a nearby provincial park, but again, we were rebuffed, this time by park officials. Parks, be they national, state/provincial or municipal, have a love-hate relationship with geocaching. On one hand, the game gets people outside and exploring. On the other hand, those perfect hiding places take hundreds of geocachers off established trails, damaging the very wilderness the park is protecting.

Some parks have banned geocaching entirely, while some have embraced it. Others have compromised and either keep a tight leash on the location of approved geocaches or offer their own suite of geocaches to find.

Those in-house geocaches are typically kid-friendly and located in easily accessible spots around main park facilities. Often a booklet is provided with clues, and once all the caches have been found, children can return them to park officials for a prize. This type of geocaching isn’t as rewarding as its progenitor, but it’s ideal for younger kids and families not keen on hiking.

Thankfully, geocachers are a wily lot, and you will find many caches in the vicinity of most parks. And non-park wilderness areas are a bonanza for geocaching with a wide range of types and difficulties available, often accompanied by the most incredible views.

Furthermore, geocaching is not relegated to the countryside. Punch up any urban area on the www.geocaching.com map, and you’ll uncover hundreds of caches. They make the perfect excuse for getting active at home or on the roam and justifying that ice-cream treat or s’more afterward.

In retrospect, my initial doubts about geocaching were unwarranted. Never underestimate the thrill of a chase. Just finding a cache is fulfilling, and our kids compete with increasing vigor each summer, as do my wife and I.

Best of all, you no longer need a GPS to play. All smartphones are GPS-enabled, and, as expected, www.geocaching.com has an app for that. It even works off-grid as long as you download caches before you leave.

Just don’t forget your dog.

Jamie, Jake and Sophie discover a geocache near Sandy McNabb Campground in Kananaskis Country, Alberta.

Common Geocaching Terms

BYOP: Bring your own pen or pencil

CO: Cache owner

DNF: Did not find

FTF: First to find

SL: Signed logbook

SWAG: Stuff we all get (tradable treasures found in a cache)

TFTC: Thanks for the cache (used when logging a find)

TNLN: Took nothing, left nothing (used by geocachers who don’t trade treasures)

Muggle: Non-geocacher (adopted from the Harry Potter books)

Other GPS Games

Pokémon Go: Mobile game where users capture Pokémon in what appears to be the real world.

Waymarking: Locating and learning about interesting locations (see virtual cache).

Letterboxing: Using clues published online or shared by word of mouth to find a letterbox containing a personalized stamp of which you take an impression to prove you found it. Some include GPS coordinates making these also geocaches.

Wherigo: Users complete a series of actions (known as a cartridge) with success in each enabling progress to the next and ending with a geocache.

For More Information

Geocaching HQ, www.geocaching.com

OpenCaching North America, www.opencaching.us

TerraCaching, www.terracaching.com

Waymarking, www.waymarking.com

Whereigo, www.wherigo.com

Born and raised in St. Jacobs, Ontario, Jamie Schmidt lives with his wife, Stephanie, and two children, Sophie and Jake, in Calgary, Alberta, where they enjoy camping in the mountains, on the prairies and all points in between. A former environmental hydrogeologist turned oil and gas geologist, Jamie has spent the past dozen years as a stay-at-home dad while pursuing a writing hobby through his personal blog and in print.

Born and raised in St. Jacobs, Ontario, Jamie Schmidt lives with his wife, Stephanie, and two children, Sophie and Jake, in Calgary, Alberta, where they enjoy camping in the mountains, on the prairies and all points in between. A former environmental hydrogeologist turned oil and gas geologist, Jamie has spent the past dozen years as a stay-at-home dad while pursuing a writing hobby through his personal blog and in print.