What better way to celebrate the 150th anniversary of America’s neighbor to the north than a grand adventure on the continent’s longest highway?

Paul McCartney sang about “the long and winding road,” but I’m here to tell you, he didn’t know the half of it. I’ve just returned from a coast-to-coast trip on the Trans-Canada Highway, the longest uninterrupted route in North America. While I’ll get into specifics in a moment, for now let’s just say our trip from Vancouver, British Columbia, to Halifax, Nova Scotia, was an RV adventure of epic proportions. Whether you choose to hitch up your trailer and drive the highway from coast to coast, as my friend Mike and I did, or just follow along a short segment, one thing is for certain. The trip will leave you with lifelong memories and a new appreciation for America’s neighbor to the north.

The Road Ahead

Every road trip needs a road, and at nearly 5,000 miles, the Trans-Canada Highway is a great road indeed. Its sections of modern divided highway are broken up by many segments of two-lane blacktop that seem to have changed little since the transcontinental route officially opened in 1962. For two guys looking for an out-of-the-ordinary RV journey, the Trans-Canada Highway proved to be ideal, with every passing mile creating lasting memories in terms of both stunning scenery and remarkably friendly locals — not to mention the camaraderie that can only come from good friends embarking on a grand adventure together.

As much as I love everything about being on the road, Mike and I fully expected that there would be problems. What neither of us imagined, however, was that the challenges would start so soon. Just trying to get across the Canadian border north of Seattle turned out to be problematic when an overzealous border guard grilled us relentlessly.

We were eventually ordered to pull over and report to the counter inside where they deal with such scofflaws. When we finally reached the head of the line, we had what turned out to be a very pleasant chat with the officer’s supervisor, who admitted he was envious of our trip. He soon cut us loose, and Mike and I set off in high spirits.

Highway to Hells Gate

From a navigational standpoint, the part of the trip through British Columbia was the easiest. We found the Trans-Canada Highway — Highway 1 in these parts — thanks to its distinctive green route signs emblazoned with a white maple leaf. From there, it was simply a matter of pointing our rig east.

This section of the highway is also hands-down one of the most scenic. From the outskirts of Vancouver, the road winds through the farm belt around Chilliwack (an odd name for one of Canada’s warmest cities) before heading up into the densely forested mountains east of Hope.

Putting in regular appearances throughout this stretch was the Fraser River. As we drove upstream and entered the depths of Fraser Canyon, we encountered the rapids flowing through the 110-foot-wide rocky gap known as Hells Gate, an obstacle that proved to be the vexation of thousands of prospectors during the area’s 1857 gold rush. For a closer look at this tumultuous stretch of river, we recommend taking a trip in the enclosed gondolas of the Swiss-built aerial tramway.

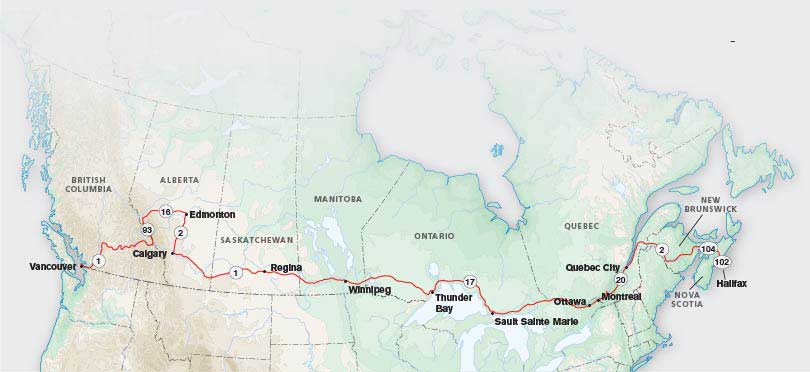

Starting in British Columbia, the Trans-Canada Highway journeys east through the country’s 10 provinces. The author and his travel companion made their way through seven of them.

A Must-Do Detour

Our next destination required a detour off the Trans-Canada Highway. Having long heard about how spectacular Banff and Jasper national parks are, we couldn’t come this close without seeing for ourselves. Unfortunately, you couldn’t prove how utterly breathtaking the Canadian Rockies are by our experience. Although we stayed in the area for several days, low clouds obscured our views of the dramatic peaks the whole time.

Not that this side trip was a complete washout, however. We drove the 144-mile Icefields Parkway several times, stopping to ogle landmarks like the 80-foot drop of Athabasca Falls, where the water’s pale blue hue created a scene not unlike a watercolor painting.

To get a look at the glaciers that give the Icefields Parkway its name, we also stopped at the Columbia Icefield Discovery Centre. From the deck we had sweeping views of the massive icefield, the largest of its kind south of Alaska. To get a closer look, sign up for one of the sightseeing tours aboard the humongous Ice Explorer buses that trek onto the surface of the glacier itself.

Icons of the Canadian prairie, pronghorn can outrun any creature in North America.

Prairies and Pronghorn

The sun that had eluded us in the national parks returned as we passed through the outskirts of Edmonton and Calgary on our way to rejoin the Trans-Canada Highway, where we once again turned east toward the Great Plains.

This was farm and ranch country, with fields full of corn and cattle ambling over gently rolling hills. A Canadian marketing pamphlet, hoping to lure European settlers in the early 1900s, called this “the last, best West.” One look at the pronghorn we saw bounding across this wide-open landscape was all it took to convince us that description still rings true.

To learn more about the lives of the native Canadians that have long called this prairie home, consider stopping off at Blackfoot Crossing Historical Park just south of the Trans-Canada Highway about 60 miles east of Calgary. Overlooking the Bow River, you’ll find a modern architectural masterpiece of a building, filled with exhibits designed to introduce the history of the Blackfoot people.

Carved by the Red Deer River, Horse Thief Canyon is a dramatic example of the badlands that blanket southeastern Alberta.

Good Times in the Badlands

In the more distant past, this area was home to giant lizards, and paleontologists regularly find their bones protruding from eroded hillsides of the nearby Canadian Badlands.

To see some of their discoveries, take the detour north to the Royal Tyrell Museum of Paleontology, 4 miles outside the town of Drumheller. This is also a good place to stretch your legs on one of several nearby hiking trails through the badlands that border the Red Deer River valley.

If you’d like to get a hands-on feel for the paleontologist’s life, visit Dinosaur Provincial Park, just north of the highway at Brooks. Here you can participate in an actual dinosaur dig, helping to locate and recover buried fossils that haven’t seen the light of

day for 75 million years.

Mike and I continued toward the city of Medicine Hat, a great name for a town that refers to the majestic eagle-feather headdresses worn by Blackfoot medicine men. Because we’d made better time than expected, we abandoned our plan to stop here for the night and pushed on into the province of Saskatchewan.

On the province’s western side, the Bow River flows into turquoise-blue Bow Lake, presenting stunning photo opportunities just off the Icefields Parkway.

Meandering Toward Moose Jaw

Leaving the world’s tallest tepee in our rearview mirror (at 214 feet, you can’t miss it), we soon crossed the Alberta-Saskatchewan line. Since most of Saskatchewan doesn’t observe Daylight Saving Time, we picked up an extra hour to see waving wheat and lots of it. As with America’s farm country, many of the once-thriving communities here had been reduced to a mere cluster of dilapidated houses and shuttered storefronts.

The town of Swift Current, 135 miles east of Medicine Hat, was much more of a going concern. Along with the expected trappings of modern life, like a Tim Hortons (a coffee shop that’s a Canadian institution), we saw a long line of dealerships with rows of shiny new tractors and combines for sale. As I said, this is farm country, but the extensive inventory these dealers had on hand made me wonder how many of these pricey machines they could possibly sell in any given year.

In another two hours, we were approaching the outskirts of Moose Jaw (another great name for a town), as the sun was sinking below the western horizon.

The Icefields Parkway, Highway 93, cuts a 145-mile swath through the Rockies between the mountain towns of Lake Louise and Jasper.

Life in the Slow Lane

Mike and I were up early the next morning, eager to get to our next destination, Winnipeg, Manitoba. Like Texas, Saskatchewan seems to go on forever, and we hit some traffic in the capital city of Regina. When Mike used his phone to Google “Regina,” he discovered the outpost was once called Pile of Bones, a name we both agreed had a much more colorful ring to it.

We crossed the Saskatchewan-Manitoba line and pressed on past fields of sunflowers to Winnipeg, where we soon discovered the campground had lost our reservation. All that was quickly rectified, however, and we settled in to enjoy a day off the road.

The next morning we headed to the Royal Canadian Mint. All of the country’s coinage is struck here, including unique versions of the loonie and toonie (one- and two-dollar coins, respectively) designed to celebrate Canada’s sesquicentennial. The tour of the plant turned out to be fascinating and included the chance to heft an actual gold ingot under the watchful gaze of an exceptionally friendly but well-armed guard. My only complaint was that they didn’t give out samples!

Visitors come face to face with dinosaur skeletons at Drumheller, Alberta’s Royal Tyrrell Museum, Canada’s only museum dedicated

exclusively to paleontology.

Elusive Antlers

After an enjoyable day off, we were ready to hit the pavement bright and early the next morning. Next stop: Thunder Bay, Ontario.

As we crossed the Manitoba-Ontario line, the Trans-Canada Highway’s route number changed from 1 to 17. Here the road began to rise through increasingly rolling countryside and past the once-important gold-mining town of Kenora (originally named Rat Portage) on the northern shore of Lake of the Woods.

Speaking of bodies of water, the country we were traveling through was full of them, from small ponds to large lakes. This is where I began my borderline-obsessive search for the noble moose the yellow highway signs were warning us about mile after mile. Both Mike and I studied the shoreline of every waterhole. With nothing to show for our eagle-eyed efforts, we began to wonder if perhaps it was the local moose’s day off.

We rolled into Thunder Bay late that afternoon, as bruise-colored clouds were building up over the shores of Lake Superior. Our three-day stay here just happened to coincide with the RV park’s Canada Day celebration (think Fourth of July, and you’ll get the picture), complete with an impressive fireworks display.

Bears and Barbecue

With those festivities over, it was timeto ease on down the road once again. Our route took us along the north shore of Lake Superior toward the border town of Sault Sainte Marie (say “soo-saint-marie”).

We passed through the small town of White River where Royal Canadian Army Lieutenant Harry Colebourn, on his way to fight in World War I, purchased a black bear cub he named Winnie in honor of his Winnipeg home town. After the cub was smuggled across the Atlantic, Winnie became a mascot for the troops before Colebourn donated him to the London Zoo. It was there that this Canadian bear fueled the fertile imagination of author A.A. Milne, the man who created everybody’s favorite bear cub, Winnie-the-Pooh.

We continued on to the town of Marathon and the turnoff for the 725-square-mile preserve known as Pukaskwa National Park. The park protects the longest stretch of undeveloped shoreline in the Great Lakes, and if you’ve a mind to see just how cold the waters of Lake Superior really are, the sandy beach here at Hattie Cove will give you your chance.

This part of the trip also offered a unique learning experience, when a young black bear (whom we naturally named Pooh) decided to saunter across the highway in front of us. It was a moment that taught me just how quickly I could bring 23,000 pounds of truck and trailer to a halt.

As we rolled into Sault Sainte Marie that afternoon, we were greeted by what was perhaps the most idyllic weather of the whole trip. Having arrived too late to visit the Canadian Bushplane Heritage Centre, we had to make do with a couple of steaks on the built-in gas grill that came with our campsite. As we dined al fresco, Mike and I agreed that, yes, indeed, we were really roughing it.

In Nova Scotia, on the shores of the Bay of Fundy, low tide strands fishing vessels in the picturesque community of Hall’s Harbour.

Water, Water Everywhere

We were up early again the next morning, as we continued east on the Trans-Canada Highway along the north shore of Lake Huron. Of all the Great Lakes, Huron is the second largest in terms of surface area, a fact that at first doesn’t seem possible when you look across the narrow North Channel to Manitoulin Island, the world’s largest island in

a freshwater lake.

To make things just that much more interesting, Manitoulin Island is so big it has its own series of more than 100 lakes, many of which have their own islands, some of which have their own lakes. The thought of having a freshwater lake on an island in a freshwater lake on an island in a freshwater lake was enough to make our heads spin.

Pondering such geographical oddities, we rolled through small towns like Blind River and past old farms now reverting to forests. We reentered civilization again at Sudbury, a former mining town built to take advantage of the area’s large deposits of nickel ore, one of which was discovered by none other than Thomas Edison.

From there we ran along the Quebec border on our way to Renfrew, an hour west of Ottawa, Canada’s capital city, where we stopped for the night.

A Funny, Saintly Town

With fewer than 1,000 miles to go to our final destination of Halifax, Nova Scotia, we hit the road to Montreal. The Trans-Canada Highway — here known as Route 20 or the Route Transcanadienne — goes smack-dab through the heart of the city, and between the heavy traffic and difficult-to-decipher French road signs, my nerves were fraying. We somehow emerged on the other side of the city unscathed, thanks to Mike’s cool head and crackerjack navigational skills.

We skirted downtown Quebec two hours later, and continued past peaceful farm fields and orchards along the southern shores of the wide St. Lawrence River. We made a sharp turn southeast at Rivière-du-Loup (“River of the Wolf”) to follow the Trans-Canada, now known as Highway 2, past one small town after another, most of which seemed to have the word “Saint” in their names.

New Brunswick’s Fundy National Park, home to the world’s highest tides.

While we commented on this profusion of heavenly monikers, we didn’t think too much about it until we came to the exit sign for the village of Saint-Louis-du-Ha!-Ha! (yes, the exclamation points are actually part of the name). If the town council’s goal was to elicit outright laughter from passersby, I can tell you, they succeeded.

Halifax or Bust

Crossing the border into New Brunswick, the gray, rainy skies returned. This part of the Trans-Canada Highway parallels the St. John River, brushing the northern tip of Maine near Caribou and Presque Isle in the process. It also comes close to Fundy National Park, named for the Bay of Fundy, a world-famous inlet known for its 50-foot tides. Getting to the park requires a 45-minute detour, but it’s a must-see if you have the time.

Somewhere around Amherst, the Trans-Canada Highway takes on yet another new identity as Route 104. With more than 4,000 miles and seven of Canada’s 10 provinces under our belts, we were ready to be done, so we cut off on Route 102 to reach Halifax.

Now all that was left was the very long and winding trip back home.

If You Go

The Trans-Canada Highway is North America’s longest highway, and from British Columbia

to Nova Scotia, we traveled most of it, with a detour in the Rockies. While there are stretches where campgrounds and gas stations are few and far between, driving the highway gives the feeling of being on a true middle-of-nowhere adventure without having to sacrifice comfort and amenities. RV accommodations range from national and provincial campgrounds to privately owned parks. To find them, go to www.goodsamcamping.com and search by city and province.