Sainte Genevieve, America’s oldest French Colonial village, welcomes visitors to historic homes, period gardens, and charming shops and galleries

When my husband, Guy, and I decided last year to visit Sainte Genevieve — the oldest permanent European settlement in Missouri and only original French Colonial village left in the country — it was with the plan to spend a couple of leisurely days walking back through time along quaint streets. More 18th- and early 19th-century French Creole vertical-log homes survive here than anywhere else, many of them surrounded by elegant period flower gardens. A number of restored buildings are open to visitors in the six-block National Landmark Historic District, with legislation proposed to make it a National Historic Site.

A massive “tow” of 25 barges (more than 22,000 truckloads) makes its way up the Mississippi River at historic Sainte Genevieve.

Sainte Genevieve is an hour south of St. Louis, set amid rolling, tree-statued hills along the Mississippi River. In a state with many fine tourist destinations, the town is among the most popular. More than 80,000 visitors come every year to take in Sainte Genevieve’s rich history and attractions: dozens of shops and boutiques, art galleries and restaurants, a wine trail featuring 10 wineries, two microbreweries, a distillery and even a tiger sanctuary.

There’s hiking and picnicking at several parks and natural areas where views of the river and surrounding hills are sublime. And should you want to cross the river to Illinois, you can ride the ferryboat. One has been operating here for more than 200 years.

For us, Sainte Genevieve is only an hour from home, so we’ve visited before; however, this time would be different. It would include a much rarer historical experience: the 2017 total solar eclipse, the first to cross the United States from coast to coast in nearly a century.

The 1790 Green Tree Tavern, Saint Genevieve’s oldest vertical-log building, is open seasonally for touring.

A total eclipse occurs when the moon passes between the sun and earth, blocking the sun from view and casting a shadow on the earth. Traveling at some 1,600 miles per hour, the shadow would this time sweep a 70-mile-wide path diagonally across the country, from Oregon to South Carolina. The trip across 10 states would take just 94 minutes.

A total solar eclipse hadn’t been seen in southeastern Missouri since July 7, 1442. For those keeping track, that’s before the first French settlers arrived, and half a century before Columbus stepped ashore in the New World). Of course, the scientific community had known for decades that one was coming. A few months in advance, word began to spread, and we learned that Sainte Genevieve would be on the “center line,” meaning “maximum totality” for two minutes and 40 seconds, the longest of anywhere along the route.

We made sure to be there on the big day — August 21, 2017 — and along with more than 6,000 other visitors, plus most of the town’s 4,410 residents, we watched the thrilling Great American Eclipse. For many, it was a once-in-a-lifetime experience.

French Creole Corridor

Because we knew the town would be overrun with visitors the day of the much-heralded event, and many attractions would be closed due to those in charge also wanting to witness the spectacle, we visited in advance. We recommend stopping first at the Sainte Genevieve Welcome Center in the heart of the historic district where exhibits and a short film tell the story of the town’s nearly 300-year history.

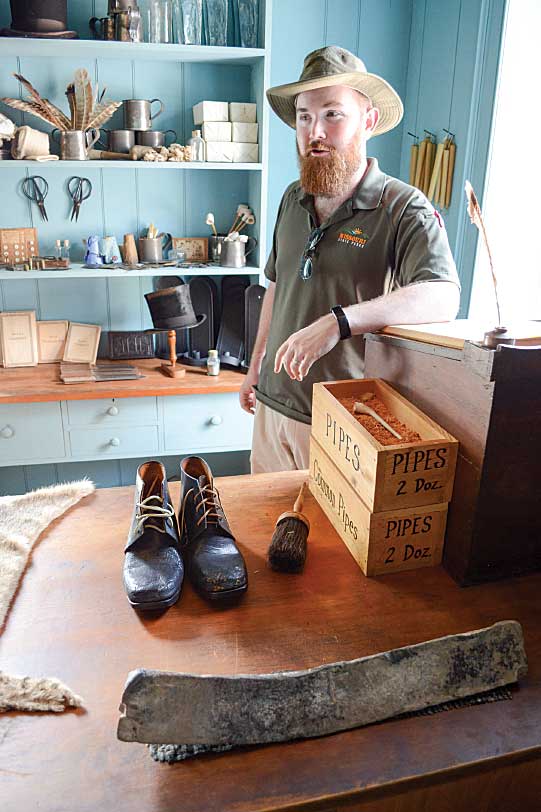

Guide Taylor Harvin “keeps store” at the famous Felix Vallé (Vai-yea) House State Historic Site. Among the furs, candles and shoes is the object in the foreground, an ancient lead ingot.

Sainte Genevieve lies at the south end of the 65-mile-long French Creole Corridor, old Illinois Country, which occupied much of the Mississippi River Valley and included other early French communities east of the river. Cahokia, in Illinois, is at the corridor’s north end, and in colonial days the stretch between Cahokia and Sainte Genevieve was a veritable French world: language, religion, laws, even marriage and inheritance customs and farming practices had been transported from the Old World.

Begun as an offshoot of older communities east of the river, Sainte Genevieve was settled around 1735 by French Canadians who came to farm the rich river-bottom soil, fur-trap and mine lead (Missouri would become a global producer of lead and Sainte Genevieve the port from where it was shipped). Within two decades of the town’s founding, France and England were at war. Anticipating defeat, in 1762 France secretly ceded land west of the Mississippi to its ally, Spain.

Though under Spanish rule for nearly 40 years, Sainte Genevieve kept its French character and culture — in fact, the earliest buildings you see today were built during this time. Then, once again, in 1800, the town found itself belonging to France, but by this time a flood had destroyed the original settlement, and in 1785 the town had been moved to its present site, about 3 miles north.

French control was short-lived, as in 1803 Napoleon sold the Louisiana Purchase (including what would be Missouri) to the United States, and Sainte Genevieve residents became American citizens. Soon there came an influx of Anglo-Americans, then Germans, merchants, lawyers and entrepreneurs who built their own styles of homes and businesses. But the 18th-century colonial architecture was preserved, side by side with newer structures, as you see it today.

French Creole buildings featured sturdy, vertical cedar-log walls and steeply pitched roofs above massive Norman trusses, patterned after the style popular in Normandy, France, and later in French Canada. Two types of the architecture characterized the corridor: poteaux-en-terre (posts in the ground) and poteaux-sur-sol (posts on a sill of brick or stone). Few of either type are standing today, and only Sainte Genevieve retains the appearance of an 18th-century French Creole village. Several of the early homes are still occupied as residences; others are furnished as they would have been more than two centuries ago and are open for guided tours.

Colonial Roots

The “keeping room,” of the Louis Bolduc House (1792), where residents cooked, ate and slept in the same room.

Of particular interest are the Beauvais-Amoureux House and Bequette Ribault House, examples of the rare poteaux-en-terre architecture (only five remain in the entire country). At the Beauvais-Amoureux, you get a bird’s-eye view of the town as it appeared in 1832 at the 100-plus-square-foot diorama. Both homes overlook a wide cornfield, now privately owned, that in colonial days was divided into long, narrow strips of land perpendicular to the river, each with a waterfront and cultivated by local farmers with teams of oxen.

A poteaux-sur-sol, the Jacques Guibourd Historic House illustrates the cultured tastes of its builder (a native Frenchman) in dozens of elegant Louis XV and XVI antiques. We were led up steep, narrow stairs to the attic for a look at the impressive forest of Norman trusses, made of hewn logs and wooden pins.

The Bolduc House, also a poteaux-sur-sol and among the earliest in town, is “widely recognized as the most authentically restored French Colonial house in the country,” says tour guide Roseanne Ahne. Typical of the time, flower and vegetable gardens stretch behind the house.

The Federal-style Felix Vallé House includes a mercantile, stocked today as it would have when Vallé ran it, with blankets, pewter mugs and tanned animal hides. Vallé was one of the town’s wealthiest residents, and his widow, Odile, donated much of the estate ($18,000) toward construction of the Catholic Church of Sainte Genevieve.

With a steeple that soars 190 feet above the road, the church is magnificent, the third to stand on the site. The parish was founded in 1759, and a log church was built on Le Grand Champ. It was dismantled and moved here in 1794, then replaced by a stone church dedicated in 1837. The church you see today — brick, lavish with paintings, statues and gem-hued stained-glass windows — was dedicated in 1880 and enlarged in 1911.

The town’s museum, located across the street from the church, was built in 1935 as part of the bicentennial celebration, and all artifacts reflect Sainte Genevieve area history. Among these are Native American items and models of birds attributed to famous ornithologist and painter John James Audubon, who lived here briefly in the early 19th century. South of town a 13-mile loop trail named for the naturalist winds through a wilderness within the Mark Twain National Forest, where he collected birds to paint.

One of the oldest brick buildings west of the Mississippi houses the Old Brick House restaurant, serving breakfast, lunch and dinner.

En route to the trailhead are a number of other local attractions: Crown Valley Winery, Crown Valley Brewery, Chaumette Vineyards and Winery, and Charleville Vineyards Winery and Microbrewery. Crown Ridge Tiger Sanctuary, home to four rescued tigers, welcomes visitors for a variety of tours.

Total Solar Eclipse

As eclipse day approached, Sainte Genevieve Tourism made elaborate preparations. There would be free “reserved 360-degree viewing” at the town’s three parks. We and 4,000 others reserved space at the Community Center, with everyone allotted 4 square feet. A fleet of school buses would transport visitors to their viewing site from seven different parking areas.

Eighty RV sites were added to already existing sites. Eclipse “followers” were flying into St. Louis from as far away as Australia and Japan for the event, some of them renting RVs for their stay.

Everyone worried a little about the weather: There could be cloud cover or, worse, rain for the “eclipse of a generation.” But the day dawned hot and sunny, though with clumps of rain-bruised clouds drifting slowly overhead.

We arrived in town three hours before the 11:50 a.m. “contact,” when the moon would take its first “bite” out of the sun. Cars in the parking lot represented more than a dozen U.S. states plus a few Canadian provinces. Among our neighbors were David and Cheryl Mehl from Houston, and had we chosen them, we couldn’t have done better. An engineer, David had brought along electronic devices to, among other things, measure the sun’s altitude at “totality” (64 degrees) and precise duration of totality (1:18:05 p.m. to 1:20:45 p.m.).

By 12:50 p.m., with the moon closing in, the sun — viewed through eclipse glasses — had become a slim orange crescent, though still blinding to the naked eye. On the ground, through the leaves of a paper bark birch nearby, a display of reverse crescents appeared, like images viewed through a pinhole camera. Clouds drifted across the sun and moved on. The light grew strange, though not like dusk, more like “an undusk,” our Maryland neighbor and I jokingly agreed. Just before totality, David pointed out “shadow bands” moving across the grass, light dancing for a few seconds like snakes, he said, or gentle waves.

Then, like the second hand on a clock, the moon clicked into place, and the world went dim, dark as late evening, and clouds forming a ring around the horizon turned bright pink. Cheers and gasps of awe went up from the crowd. Time to take off the eclipse glasses and look bare-eyed at the celestial spectacle: the “diamond ring,” the sun’s loopy-white corona dazzling as a halo around the black-disk moon, a handful of bright stars and planets now visible.

I had read that odd things happen during a total eclipse: birds stop singing, spiders tear down their webs, and gray squirrels retreat to their dens, according to a study by the California Academy of Science. What we noted was that immediately the temperature dropped (from 108 to 94 degrees, we learned later), and night insects, cicadas, crickets and katydids began their rhythmic singing.

For 160 seconds we watched a display of pure magic. Then the moon inched off the slimmest crescent of sun, eclipse glasses went back on, and the insects stopped singing. An hour and a half later, the show was “totally” over (sorry, I couldn’t resist).

It was an amazing experience — and what’s best, southeast Missouri won’t have to wait 575 years to see another one. The next total solar eclipse, this one crossing over Mexico, then Texas, en route to Maine, will pass through on April 8, 2024. We’re already making plans.

WHERE TO STAY & PLAY

WHERE TO STAY & PLAY

SAINTE GENEVIEVE

West of town on Highway 32, Hawn State Park has 25 sites with 30- and 50-amp electric service, a dump station, picnic area and playground. Water is available from April through October with spigots throughout the campground and shower facilities. Open year-round; $21 to $23 per night.

North of town on Route OO, Hidden Valley RV Park offers 17 sites with full hookups and laundry facilities. Open year-round; $35 per night, $150 per week.

The surrounding area has dozens of RV parks and campgrounds. To find them, use the search tool on the Good Sam Club website.

For history buffs, the Sainte Genevieve Welcome Center offers $15 “passports” to five sites — the 1792 Beauvais-Amoureux House, 1806 Jacques Guibourd Historic House, 1808 Bequette Ribault House, 1818 Felix Vallé State Historic Site and the Sainte Genevieve Museum. Admission is separate to the 1792 Bolduc House Museum, which includes the 1820 Bolduc-LeMeilleur House and 1820 Linden House, where the $8 tickets are purchased.